| The Moayyeri Ancestors The Wali Ancestors The Bahman (Qajar) Ancestors The Behnam Family | The Zarrinkafsch-Bahman (Qajar) Family |

The Behnam Family

The Behnam Family was a dynasty of bureaucrats in state service since the beginning of Qajar rule. Its members were mainly mostowfis or tax accountants working for the financial apparatus and married into the Bahman-Qajar princely line as well as into the families of the Princes Moezzi and Salour.

The House of Behnam - Peers of Persia

Since the very beginning of Qajar rule the government was divided into an army (lashkar) and administrative (divan) part. Agha Mohammad Shah’s years as hostage at court of Karim Khan Zand in Shiraz showed him the necessary of a running administration. And although he trusted firstly in “Men of the Sword” (ahl-e seyf) the founder of the dynasty paid great attention and respect to “Men of the Pen” (ahl-e qalam). Thus, he made the emirs and khans especially of his own tribe military commanders and provincial governors, but gave key positions in fiscal administration to members of the old settled Persian hereditary bureaucratic families. Because the mostly nomadic Turkic chieftains and warlords, the early Qajar state based upon in its military organisation, often could neither read nor write, and even were not familiar with the Persian tongue, the officials of Persian offspring were the best allies in a central government administration.

I. The Caste of Mirza

A characteristic of this class of "men of pen" was the Mirza (“bureaucrat”). Written before the first name, this title marked originally a man with skills in writing with a special but not necessarily great knowledge. He mainly was in governmental service or tried to enter into, and therefore could be treated as “clerk”. The possibility of making career was relatively good because the state had a great request in men who could read and write. With a beginning monthly salary of five to six tumans they got the double income than a servant of the royal household. The mirzas were responsibly for administrative duties and private matters of the large imperial court, as well as they worked in governmental service for the central and provincial fiscal administration and the military sector.

With no special seat of office or bureau these dignitaries worked from their homes and residences and therefore they regarded their office as a family job and government files as private property, giving them from father to son.

Keeping their interests over generations and creating an own short script hidden secretly for their government files and revenue archives the class of mirzas finally was a caste of its own with several cliques of family clans related to each other. This family continuity came at least from the pursuit to safe special post and the wealth connected with for the own family and keep them for generations within the family. So, in governmental service it was easier to secure their sons’ careers too and try to cast the son of a diseased official with his father’s post. In addition to that endogamy was widespread and the bureaucratic families tried to marry within their family or group or ally with the imperial dynasty, to protect their status and rank.

This continuity in family and occupation helped to increase an accumulation of power and posts. And at during Nasser od-Din Shah’s reign the mirzas were not only found in urban fiscal post but in the provincial ruling elite, too, and here as deputy governors (nayeb) and viziers (vazir), especially. Although at first the castes of mirzas and khans were separated strictly, it became common to mix both titles and “men of the sword” could become “men of the pen” and vice versa, finally. So among the mirzas the heads of any department higher in rank were also titled as “Khan”.

Climbing up the social strata every family took a special sobriquet which at least often became the family name, based on origin, descending or title. This happened because in Iran there was no tradition of family names like in Europe but only personal names, titles, appellations and sobriquets according to place of birth, occupation, etc. The name consisted of the traditional Islamic parts of a first name (esm), a sobriquet (konyeh), the patronymics or filiations (nesab), a name of origin (nesbeh) and sometimes a personal title (laqab). And like the old families of local lords the bureaucratic patricians conserve a tradition of genealogy with wide extending family trees until Safavid times and beyond, which preserve a distinct proud feeling of being true Persian or Iranian (iraniyat).

Only some mirzas lived from inherited or acquired real estates but mostly from salaries and sinecure. Because the offices were only granted for the time of a year and it was not sure to get the same post the next year, state servants more and more bought land, erected huge mansions and started the way of life of the old class of fiefdom holders (toyuldaran) and petty rulers, which was connected with power and prestige till the 20th century.

But despite their immense influence at court and in government, the bureaucrats only were servants of the absolute shah and the sovereign could appoint and depose them as he wanted. Therefore the mirza’s fate and that of their families always depended on the goodwill of the monarch. Enmity and foes between the different fractions around the shah favoured corruption, bribery and nepotism. Thus, the most influential post were close connected with the person of the shah and even the young sons of the aristocracy were placed in posts close to the monarch, like in the shah’s guard (gholam-e shah) or private chamberlain (pish-khedmat-e khass), which directly opened the way to power.

Royal favour (iltifat) extended from the appointment to a special post (mansab) with a fixed salary (mawajib), a provision (suyursat) and pension (mustamarri) over granting tax-free estate (toyul) to symbolic gesture of granting a robe of honour (khelat), a decoration (neshan), an amount of money (sala) or a title (laqab).

Most of these titles generally were bounded on a person, not hereditary and limited for the time in office, maximal the bearer’s lifespan. If the bearer of a title diseased or got a new laqab, his former title was free to be appointed to another person. Thus, during his lifetime one and the same man could bear more than one title. But if a special title remained in the same family over generations, which often took place among rich and prominent princes and notables, the appointment did not follow automatically. The title had been given by the shah after a gift of great value to the shah (pishkesh). And it was possible that not the eldest son but another family member was chosen by the shah. A person was known in public often only by his title and only addressed this way.

Thus, titles with the Arabic Genitive-Suffix “os-Soltan” ([of] the Ruler) were granted to worthy members of the imperial entourage, while those with “os-Saltaneh” ([of] the Rulership) were connected with public life at court; those with “od-Dowleh” ([of] the State) with the government and those with “ol-Molk” ([of] the Realm) or even “ol-Mamalek“ ([of] the Empire) with administration. Until the end of Nasser od-Din Shah’s reign (r. 1848-1896) there did not exist more than 200 of these honorary titles mostly given to the many royal princes but also to military commanders and to high dignitaries at court.

Keeping their interests over generations and creating an own short script hidden secretly for their government files and revenue archives the class of mirzas finally was a caste of its own with several cliques of family clans related to each other. This family continuity came at least from the pursuit to safe special post and the wealth connected with for the own family and keep them for generations within the family. So, in governmental service it was easier to secure their sons’ careers too and try to cast the son of a diseased official with his father’s post. In addition to that endogamy was widespread and the bureaucratic families tried to marry within their family or group or ally with the imperial dynasty, to protect their status and rank.

This continuity in family and occupation helped to increase an accumulation of power and posts. And at during Nasser od-Din Shah’s reign the mirzas were not only found in urban fiscal post but in the provincial ruling elite, too, and here as deputy governors (nayeb) and viziers (vazir), especially. Although at first the castes of mirzas and khans were separated strictly, it became common to mix both titles and “men of the sword” could become “men of the pen” and vice versa, finally. So among the mirzas the heads of any department higher in rank were also titled as “Khan”.

Climbing up the social strata every family took a special sobriquet which at least often became the family name, based on origin, descending or title. This happened because in Iran there was no tradition of family names like in Europe but only personal names, titles, appellations and sobriquets according to place of birth, occupation, etc. The name consisted of the traditional Islamic parts of a first name (esm), a sobriquet (konyeh), the patronymics or filiations (nesab), a name of origin (nesbeh) and sometimes a personal title (laqab). And like the old families of local lords the bureaucratic patricians conserve a tradition of genealogy with wide extending family trees until Safavid times and beyond, which preserve a distinct proud feeling of being true Persian or Iranian (iraniyat).

Only some mirzas lived from inherited or acquired real estates but mostly from salaries and sinecure. Because the offices were only granted for the time of a year and it was not sure to get the same post the next year, state servants more and more bought land, erected huge mansions and started the way of life of the old class of fiefdom holders (toyuldaran) and petty rulers, which was connected with power and prestige till the 20th century.

But despite their immense influence at court and in government, the bureaucrats only were servants of the absolute shah and the sovereign could appoint and depose them as he wanted. Therefore the mirza’s fate and that of their families always depended on the goodwill of the monarch. Enmity and foes between the different fractions around the shah favoured corruption, bribery and nepotism. Thus, the most influential post were close connected with the person of the shah and even the young sons of the aristocracy were placed in posts close to the monarch, like in the shah’s guard (gholam-e shah) or private chamberlain (pish-khedmat-e khass), which directly opened the way to power.

Royal favour (iltifat) extended from the appointment to a special post (mansab) with a fixed salary (mawajib), a provision (suyursat) and pension (mustamarri) over granting tax-free estate (toyul) to symbolic gesture of granting a robe of honour (khelat), a decoration (neshan), an amount of money (sala) or a title (laqab).

Most of these titles generally were bounded on a person, not hereditary and limited for the time in office, maximal the bearer’s lifespan. If the bearer of a title diseased or got a new laqab, his former title was free to be appointed to another person. Thus, during his lifetime one and the same man could bear more than one title. But if a special title remained in the same family over generations, which often took place among rich and prominent princes and notables, the appointment did not follow automatically. The title had been given by the shah after a gift of great value to the shah (pishkesh). And it was possible that not the eldest son but another family member was chosen by the shah. A person was known in public often only by his title and only addressed this way.

Thus, titles with the Arabic Genitive-Suffix “os-Soltan” ([of] the Ruler) were granted to worthy members of the imperial entourage, while those with “os-Saltaneh” ([of] the Rulership) were connected with public life at court; those with “od-Dowleh” ([of] the State) with the government and those with “ol-Molk” ([of] the Realm) or even “ol-Mamalek“ ([of] the Empire) with administration. Until the end of Nasser od-Din Shah’s reign (r. 1848-1896) there did not exist more than 200 of these honorary titles mostly given to the many royal princes but also to military commanders and to high dignitaries at court.

Mostly found on regional and familiar bands the bureaucrats running state offices could be divided in four fractions, which protected their posts conservatively and jealously against any other pretenders. The Fars fraction was dominated by the Shirazi family, the family of Ebrahim Kalantar Shirazi, the first grand vizier of Agha Mohammad Shah and Fath Ali Shah. His clan was among the highest decorated and widespread in any resort of the early Qajar government, mostly connected with financial duties. After its members lost their favour another fraction from Persian Iraq (Eraq-e Ajam) came to prominence at court headed by the Farahani family and its clients, the Ashtiyani and Tafreshi clans. Later the fraction from Mazandaran was dominated by the Nuri family and in the time of Mohammad Shah Qajar a great part of officials came from noble families from Georgia, Erivan and Kurdistan.

Because these officials surrounded the ruler permanently, they were able to use their influence to secure posts and titles within their family and established own dynasties of bureaucrats often connected to the royal house by blood ties. Among these were the most prominent in Qajar time the Qawwami (descendants of Mirza Abol Qassem Kalantar Shirazi “Qawwam ol-Molk”), the Moayyeri (descendants of Dust Ali Khan Bastami [I] “Moayyer ol-Mamalek”), the Mostowfi (descendants of Mirza Hassan Ashtiyani [I] “Mostowfi ol-Mamalek”) and the Amini (descendants of Mirza Ali Khan “Amin od-Dowleh”) Family.

Because these officials surrounded the ruler permanently, they were able to use their influence to secure posts and titles within their family and established own dynasties of bureaucrats often connected to the royal house by blood ties. Among these were the most prominent in Qajar time the Qawwami (descendants of Mirza Abol Qassem Kalantar Shirazi “Qawwam ol-Molk”), the Moayyeri (descendants of Dust Ali Khan Bastami [I] “Moayyer ol-Mamalek”), the Mostowfi (descendants of Mirza Hassan Ashtiyani [I] “Mostowfi ol-Mamalek”) and the Amini (descendants of Mirza Ali Khan “Amin od-Dowleh”) Family.

II. The Post of Mostowfi

When with Fath Ali

Shah Qajar (r. 1797-1834) the administrative body in the central

government increased and developed to an elaborated system of

bureaucratic offices, the financial sector became its most important

part.

Now the system of taxation and revenues was the main source of fiscal income headed by a chief revenue officer called Mostowfi ol-Mamalek (“Accountant of the Empire”) who supervised several local and regional mostowfis and often acted as Minister of Finance. This man during the reign of Fath Ali Shah was Hajji Mohammad Khan Esfahani and after him his son Abdollah Khan “Amin od-Dowleh”.

Now the system of taxation and revenues was the main source of fiscal income headed by a chief revenue officer called Mostowfi ol-Mamalek (“Accountant of the Empire”) who supervised several local and regional mostowfis and often acted as Minister of Finance. This man during the reign of Fath Ali Shah was Hajji Mohammad Khan Esfahani and after him his son Abdollah Khan “Amin od-Dowleh”.

The Financial

Ministry was the Vezarat-e

daftar-e estifa ("Ministry of revenue office"), composed in four offices:

The first office was the daftar-e jozv-e jam or tax revenue office. Here a complete register (ketabcheh-ye jozv-e jam) was kept for all provinces. For each province all tax districts (boluk) were listed and the mostowfi were responsible for the national as well as provincial taxation

The next office was that of dastur al-amal or budget office. Here clerks were in charge for the annual budget of each ministry, province or department accounting a balance between collected revenues and expenses of the governors like payment of the troops in garrison as well as pensions and salaries granted by the central government.

The third office was the daftar-e avarajeh or office of assets, dealing solely with expenditures of the royal household (boyutat-e saltani). The mostowfi here had to check if all documents such as farmans for the grant of a teyul or receipt (barat) in cash or kind were registered properly.

The last office was the daftar-e mohasebeh or tax settlement office. It was in charge of the drawing up the country’s budget and had a special responsibility for collecting the tax arrears. It coordinated the incoming documents to prepare the next annual budget.

The first office was the daftar-e jozv-e jam or tax revenue office. Here a complete register (ketabcheh-ye jozv-e jam) was kept for all provinces. For each province all tax districts (boluk) were listed and the mostowfi were responsible for the national as well as provincial taxation

The next office was that of dastur al-amal or budget office. Here clerks were in charge for the annual budget of each ministry, province or department accounting a balance between collected revenues and expenses of the governors like payment of the troops in garrison as well as pensions and salaries granted by the central government.

The third office was the daftar-e avarajeh or office of assets, dealing solely with expenditures of the royal household (boyutat-e saltani). The mostowfi here had to check if all documents such as farmans for the grant of a teyul or receipt (barat) in cash or kind were registered properly.

The last office was the daftar-e mohasebeh or tax settlement office. It was in charge of the drawing up the country’s budget and had a special responsibility for collecting the tax arrears. It coordinated the incoming documents to prepare the next annual budget.

For

the increased number of employees in governmental service now a correct

and efficient system of accounting, issuing orders and giving receipts

was necessary. Therefor, in addition with this fiscal administration

two more offices were found: The office of a chief secretary or Monshi ol-Mamalek (“Secretary

of the Empire”) responsible for all royal orders and commands and the

correspondence, who headed a staff of scribes and order-writers. And an

official in charge of all state expenditures and payments with the

title of Saheb-e Divan (“Keeper of the Book”), who checked all lists with persons in state service receiving a salary.

Persia

was divided into four administration segments: Azerbaijan, Arak, Fars,

Kerman and Khorassan with several accountants or mostowfis in charge of tax

collecting and registration.

There were mainly two classes of mostowfis; those that worked for the central government and those that worked at the provincial level (mostowfi-ye mahalli) assisting the governor-generals. All of them received a fixed salary from the state. The leading mostowfis were all referred to with the title of Jenab or "Excellency". For each designated geographical area a chief mostowfi was appointed as financial director. He was in charge of particular divisions in the province but need not necessarily live in the part of the province that he was responsible for. This mostowfi was not subordinated to the Vazir-e daftar but to the governor who had appointed him.

There were mainly two classes of mostowfis; those that worked for the central government and those that worked at the provincial level (mostowfi-ye mahalli) assisting the governor-generals. All of them received a fixed salary from the state. The leading mostowfis were all referred to with the title of Jenab or "Excellency". For each designated geographical area a chief mostowfi was appointed as financial director. He was in charge of particular divisions in the province but need not necessarily live in the part of the province that he was responsible for. This mostowfi was not subordinated to the Vazir-e daftar but to the governor who had appointed him.

For

this job the mostowfi required a special education often given from

father to son. This fact supported heredity in offices. In addition the

tax registers were written in special shorthand, impossible to read for

any outstanding. And the actual tax rolls written in unbound little

booklets of very small papers (ketabcheh) were carried around in the

mostowfis’ pockets. These ketabchehs were considered as private

property and the mostowfis refused to hand them out to other government

officials. Therefore, “consequently the class of mostowfis had become a

closed shop, who closely guarded their secrets.” The

elaborated system of financial bookkeeping in Qajar time made certain

job training necessary. And the fact that the mostowfis were the only

ones familiar with tax collecting and recording made them extremely

powerful in governmental duties.

III. The Behnam Family

From the Iranian Central Province Makrazi, often named Eraq-e Ajam or “Persian Iraq” the Farahani bureaucratic clan came, including the Ashtiyani and Tafreshi families. The settled population of Persian origin and Shiite faith from this region was a good ally for the Qajar shahs in forming a central government.

Thus, at the beginning of the 19th century a man from Tafresh took his way to Tehran and entered government service in fiscal administration. His name was Hajji Mirza Esmail. Born around 1770 he was the son of Mirza Reza Tafreshi. His title Mirza made clear that he was a clerk, a literate man firm in the skills of reading and writing from Tafresh, a little town situated between the cities of Qom and Hamadan. His career started as mostowfi (tax accountant) and during the reign of Fath Ali Shah (r. 1797-1834), around the age of fifty Hajji Mirza Esmail was sent from Tehran to the Caucasus to become the civil administrator (hokmrani) of Erivan.

Thus, at the beginning of the 19th century a man from Tafresh took his way to Tehran and entered government service in fiscal administration. His name was Hajji Mirza Esmail. Born around 1770 he was the son of Mirza Reza Tafreshi. His title Mirza made clear that he was a clerk, a literate man firm in the skills of reading and writing from Tafresh, a little town situated between the cities of Qom and Hamadan. His career started as mostowfi (tax accountant) and during the reign of Fath Ali Shah (r. 1797-1834), around the age of fifty Hajji Mirza Esmail was sent from Tehran to the Caucasus to become the civil administrator (hokmrani) of Erivan.

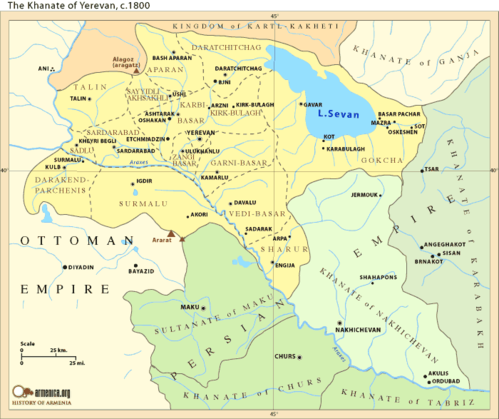

Erivan (Yerevan), today the capital city of the independent republic of Armenia, in those days was part of the Persian Empire. The Qajar tribe itself came from this region and Hossein Qoli Khan Qajar (r. 1807-1828) from a side line of the ruling house governed as semi-independent Khan with the military title of Sardar (“Commander”) on behalf of the Persian Shah.

The Erivan Khanate called Chokhur Sad in Persian bordered in the North to Georgia, in the East to the Khanates of Ganja and Karabagh and in the South to the Khanate of Nakhshivan as well as to Azerbaijan. 80 percent of the population were Muslims (Persians, Turks and Kurds) the remaining 20 percent were Christian Armenians, dominating professions in trade and commerce and therefore had good relations to the Persian administration.

During his reign Erivan was a prosperous city of about one square mile and its gardens were stretching more than 18 miles. The city counted 1,700 houses, 850 stores, 89 mosques, seven churches, ten baths, seven caravansaries, five public squares and two schools.

The military government was in the hands of Hossein Gholi Khan while the civil administration was centred on the divan or chancery, headed finally by Hajji Mirza Esmail. In 1826 he was chancellor or Saheb-e divan (lit. "Master of the Divan") and acted as a combined finance director and interior minister, administering both the city and the provincial districts. Along with the khan he appointed officials and paid the salaries, heading the administration of revenues, the taxation and payment of the army.

Also one of the most beautiful and famous mosques in Erivan was restored by Hajji Mirza Esmail, too. This mosque, decorated with wonderful green tile work, is called “Green Mosques” or Göy Masjed. Erected originally in the 18th century, it was one of the four main mosques in Erivan, famous for its polychrome façade and turquoise dome it was named after. Next to the tiled dome the building had a main prayer hall, a library and a religious seminary or medrese with 28 cells, all arranged around a courtyard. The whole complex counted 7,000 square metres and at the main portal there was a single minaret.

The Erivan Khanate called Chokhur Sad in Persian bordered in the North to Georgia, in the East to the Khanates of Ganja and Karabagh and in the South to the Khanate of Nakhshivan as well as to Azerbaijan. 80 percent of the population were Muslims (Persians, Turks and Kurds) the remaining 20 percent were Christian Armenians, dominating professions in trade and commerce and therefore had good relations to the Persian administration.

During his reign Erivan was a prosperous city of about one square mile and its gardens were stretching more than 18 miles. The city counted 1,700 houses, 850 stores, 89 mosques, seven churches, ten baths, seven caravansaries, five public squares and two schools.

The military government was in the hands of Hossein Gholi Khan while the civil administration was centred on the divan or chancery, headed finally by Hajji Mirza Esmail. In 1826 he was chancellor or Saheb-e divan (lit. "Master of the Divan") and acted as a combined finance director and interior minister, administering both the city and the provincial districts. Along with the khan he appointed officials and paid the salaries, heading the administration of revenues, the taxation and payment of the army.

Also one of the most beautiful and famous mosques in Erivan was restored by Hajji Mirza Esmail, too. This mosque, decorated with wonderful green tile work, is called “Green Mosques” or Göy Masjed. Erected originally in the 18th century, it was one of the four main mosques in Erivan, famous for its polychrome façade and turquoise dome it was named after. Next to the tiled dome the building had a main prayer hall, a library and a religious seminary or medrese with 28 cells, all arranged around a courtyard. The whole complex counted 7,000 square metres and at the main portal there was a single minaret.

After two rounds of Perso-Russian wars 1804-1813 and 1826-1828 the Persian provinces in the Caucasus were attacked by Russia, in 1828 finally conquered and the whole khanate with Erivan was annexed with the peace treaty of Torkmanchay in February 1828. From then on the Persians were forced to give up their claims of dominion in the Caucasus and Iran lost 18 Transcaucasian Provinces to the Russians: Kartli and Kakheti, Mingrelia, Abkhazia, Ganja, Karabagh, Qobba, Darband, Baku, Daghestan, Shakki, Shirvan, Maku, Avar and Ghaziq, as well as Talesh, Nakhshivan and Erivan. So, Hajji Mirza Esmail was forced to resign his post, handed over his accurate taxation rolls archive to the new masters and evacuated Erivan. His huge residence and estates in Dilaki in the Kirk-Bulagh district were annexed by the Russians and he returned to Tehran and then went back to his hometown of Tafresh.

It is common among the Tafreshis to name some persons with a special sobriquet. Added to the first name and title it could consist of designations like ’Asa (“stick”), Sabad (“basket”), Sebt (“infertile”) or Khoda (“lord”), etc. After his return from the Caucasus Hajji Mirza Esmail had brought and spent some large gold coins named Baj-Qolu (meaning “pure gold” in Georgian), and therefore people gave him that sobriquet of “Baj-Qolu” and he became popular with this name. Finally Hajji Mirza Esmail Tafreshi "Baj-Qolu" died there as an aged man and the ruins of his house in Tafresh in Vaqf-e Mahalleh district are still visible today.

It is common among the Tafreshis to name some persons with a special sobriquet. Added to the first name and title it could consist of designations like ’Asa (“stick”), Sabad (“basket”), Sebt (“infertile”) or Khoda (“lord”), etc. After his return from the Caucasus Hajji Mirza Esmail had brought and spent some large gold coins named Baj-Qolu (meaning “pure gold” in Georgian), and therefore people gave him that sobriquet of “Baj-Qolu” and he became popular with this name. Finally Hajji Mirza Esmail Tafreshi "Baj-Qolu" died there as an aged man and the ruins of his house in Tafresh in Vaqf-e Mahalleh district are still visible today.

The Khanate of Erivan in Qajar time.

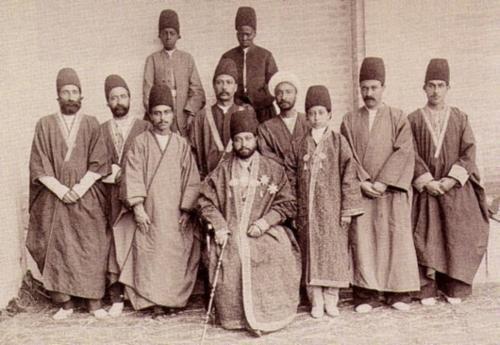

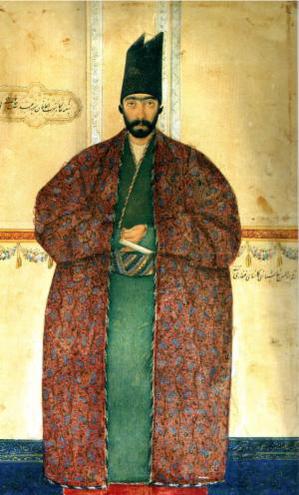

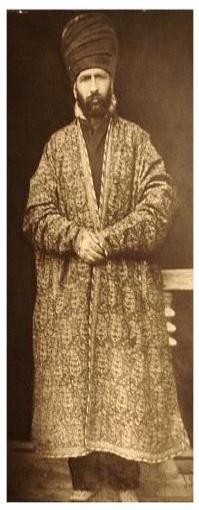

Hossein Gholi Khan Qajar of Erivan. Hajji Mirza Esmail Behnam "Baj-Qolu" painted 1819 by

Alexander Orlowski.

Alexander Orlowski.

The divan (hall of audience) in the Erivan citadel.

View of Erivan in 1796 with the citadel, the khan's residence and the "Green Mosque".

The "Green Mosque" or Göy Masjed in Erivan.

The renovated "Green Mosque" in modern time with tiled dome and main portal.

Hajji Mirza Esmail “Baj-Qolu” had issued three sons among them Hajji Mirza Ali Akbar, the father of the Behnam Family. Due to their trustworthy service as state officials the family at least was known by the name Beh Nam (lit. “Good Name”), at least translated with “trustworthy” or “honourable”.

A widespread dynasty of bureaucrats the Behnam family make career in financial administration during the whole Qajar era and intermarried into the ruling house itself. Among them some remarkable personalities can be found like Mirza Mohammad Ali, Mirza Abdollah “Monshi-bashi”, Mirza Hossein, Mirza Yussof “Salar os-Sadigh”, Mirza Hassan “Hamed od-Dowleh”, Mirza Mahmud “Dabir-e Hazrat” and Asadollah “Mani ol-Molk” as well as Emad ol-Molk, Mostashar os-Soltan, Sana os-Saltaneh, Meshkat-e Divan and Etemad os-Soltan Behnam, belonged to the clan, who all worked as mostowfis in the Financial Ministry.

A widespread dynasty of bureaucrats the Behnam family make career in financial administration during the whole Qajar era and intermarried into the ruling house itself. Among them some remarkable personalities can be found like Mirza Mohammad Ali, Mirza Abdollah “Monshi-bashi”, Mirza Hossein, Mirza Yussof “Salar os-Sadigh”, Mirza Hassan “Hamed od-Dowleh”, Mirza Mahmud “Dabir-e Hazrat” and Asadollah “Mani ol-Molk” as well as Emad ol-Molk, Mostashar os-Soltan, Sana os-Saltaneh, Meshkat-e Divan and Etemad os-Soltan Behnam, belonged to the clan, who all worked as mostowfis in the Financial Ministry.

In the time of Abbas Mirza’s regency when the Farahani viziers, father and son Mirza Issa Bozorg “Qa’em-Maqqam” and Mirza Abolghassem “Qa’em-Maqqam” (who acted as prime minister in 1835) and later Mirza Taghi Khan “Amir-e Nezam” administered the province of Azerbaijan, the Behnam family went to its capital Tabriz. Here at the seat of the heir apparent, Mirza Ali Akbar Behnam became responsible for the provincial taxation as chief mostowfi. His sons were appointed mostowfiyan-e mahalli of Tabriz and Ardabil and gained great wealth and prestige and built a wonderful family residence, the famous Behnam House of Tabriz.

When with the fall of the Qa’em-Maqqams the Esfahani family was deposed too and their post of Mostowfi ol-Mamalek was bestowed by Mohammad Shah Qajar upon the family of Mirza Yussof Ashtiyani, the new treasurer-general surrounded himself with a new clique of accountants from his home province and most of the chief mostowfis in Tehran were his kinsmen. Thus, the Behnam came back to Tehran and served in the central government. Mirza Abdollah Khan "Monshi-Bashi" was appointed "comptroller of the royal properties" (mostowfi-ye khasseh) responsible for the revenues from all crown lands (khasseh).

In the time of Nasser od-Din Shah Mirza Hossein Behnam, the mostowfi of Tabriz, returned back to Tehran as well and married there the shah's cousin, Princess Malekeh-Afagh Khanom Qajar.

When with the fall of the Qa’em-Maqqams the Esfahani family was deposed too and their post of Mostowfi ol-Mamalek was bestowed by Mohammad Shah Qajar upon the family of Mirza Yussof Ashtiyani, the new treasurer-general surrounded himself with a new clique of accountants from his home province and most of the chief mostowfis in Tehran were his kinsmen. Thus, the Behnam came back to Tehran and served in the central government. Mirza Abdollah Khan "Monshi-Bashi" was appointed "comptroller of the royal properties" (mostowfi-ye khasseh) responsible for the revenues from all crown lands (khasseh).

In the time of Nasser od-Din Shah Mirza Hossein Behnam, the mostowfi of Tabriz, returned back to Tehran as well and married there the shah's cousin, Princess Malekeh-Afagh Khanom Qajar.

The Behnam Family: Mirza Mohammad Ali Behnam, Chief Mostowfi and Financial Director of Azerbaijan with his young son Mirza Taghi Khan "Emad ol-Molk" and a staff of kinsmen, scribes and servants, Tabriz ca. 1870.

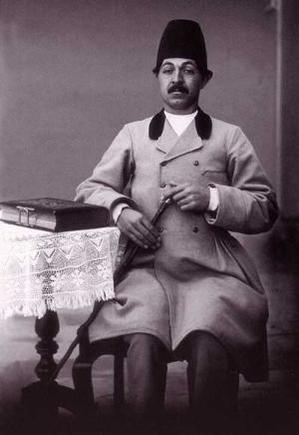

Mirza Taghi Khan Behnam in Tabriz with Crown Prince

Mozaffar od-Din Mirza and Prince Eyn od-Dowleh.

Mirza Taghi Khan "Emad ol-Molk" with his secretary.

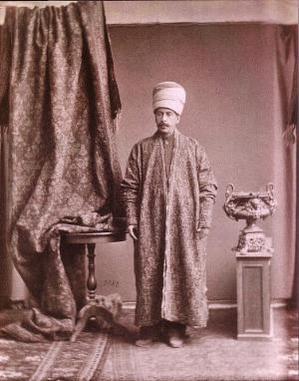

Mirza Asadollah Khan Behnam.

Mirza Hossein Behnam, Mostowfi of Tabriz. This photo

was made by Dimitri Ermakov ca. in 1880.

Mirza Abdollah Khan Behnam "Monshi-Bashi" became

Mostowfi-ye Khasseh or "comptrollerof the royal properties".

This watercolour was made by Sani ol-Molk, 1847.

Mostowfi-ye Khasseh or "comptrollerof the royal properties".

This watercolour was made by Sani ol-Molk, 1847.

The Behnam House in Tabriz with pool in front of and the great porticos.

Interiour details of the Behnam House: The receiption hall with polychrome windows and ceiling painting.

Men from the greater Behnam clan: Meshkat-e Divan and Mostashir os-Soltan Behnam.

Fathollah Behnam and his son Dariush. Ashraf Behnam and Fathollah Behnam.

Sources:

Asadollah Behnam: Khandan-e Behnam, Tehran 1962, p. 4 f.

George A. Bournoutian: The Khanate of Erevan under Qajar Rule, 1795-1828, Mazda Publishers, Costa Mesa 1992, pp. 93 ff.

Willem Floor: A Fiscal History of Iran in the Safavid and Qajar Periods, 1500-1925, Bibliotheca Persica Press, New York 1999, pp. 250 ff.

This website was created by Arian K. Zarrinkafsch (Bahman-Qajar).