| The Moayyeri Ancestors The Wali Ancestors The Bahman (Qajar) Ancestors The Behnam Family | The Zarrinkafsch-Bahman (Qajar) Family |

The Moayyeri Ancestors

Pari Soltan Khanoum Pir-Bastami's own family were our Moayyeri ancestors....

The House of Moayyeri – The Masters of the Mint

The name of the Moayyeri Family derived from their more than five generations inherited title or laqab of Moayyer ol-Mamalek, a designation which could be translated with "Assayer of the Realm", "Imperial Assayer", or at least with "Master of the Mint". The Moayyeri Family belonged during the reign of the Qajars (r. 1785-1925) to one of the most important and richest bureaucratic dynasties. Rose to power as urban notables (ayan) at the end of the 18th century under the last Safavids (r. 1501-1722) they got the title of Moayyer (i.e. “Assayer”). Under the Afsharids (r. 1736-1755) they became Moayyer-Beyg (i.e. “Lord Assayer”), in the reign of the Zands (1750-1785) Moayyer-bashi (i.e. “Chief Assayer”) and finally got under the Qajars the title of Moayyer ol-Mamalek.

I. The Persian Monetary System

In Iran like everywhere else in the world, money was used for trading and fiscal tax evaluation, and the fundament of the state’s economy. The first monetary system there was founded by King Darius the Great (r. 522-486 B.C.). The monetary system and currency of the Qajar era (1785-1925) based on that of their Safavid predecessors (r. 1501-1722), who established and standardizes new coinage (sekka) and introduced a new gold coin (ashrafi) and a silver coin (shahi). The

ashrafi was struck in accordance to the standard of the Venetian ducat and Florentine fiorino weighing 3.52 g, and with the establishment of their empire in the 16th century ashrafi coins were minted in the more than eleven local Safavid mints in Isfahan, Shiraz, Qazvin, Tabriz, Ganja, Lar, Rasht, and Mashhad, Kashan, Yazd and Howeyza. The weight of the ashrafi remained constant throughout the Safavid era; and until the second half of the 18th century the

ashrafi provided the dominant standard for Iranian gold coins. Even after it was abandoned, the name ashrafi was applied to gold coins worth one tuman of 3.52 g into the 20th century. But the nominal value of the coin in terms of silver dinars through the times changed greatly, due to the devaluation of the latter from worth about 200 dinars to 1,800 dinars.

Safavid monetary standards were expressed in terms of the tuman (lit. “10,000”), a unit of account reckoned as 10,000 dinars which have been set initially at 200

mesqals (= 920 g) of silver, meaning 200 shahis. The shahi, weighing 1 mesqal or 4.6 g was formally reckoned at 50 dinars of account. Both gold and silver were struck in numerous denominations. In addition to the shahi, quarter-, half-, double (do-shahi), and quadruple shahis were struck. After a monetary crisis in 1687-88, and devaluation in 1717 gold and silver coins were struck with lesser value in order to finance the Afghan war, and the original Safavid coin type came to an end.

After the Afghan debacle (1722-1732) causing the collapse of the Safavid Empire, Nader Shah Afshar (r. 1736-1747) introduced into Iran in 1737 a little different standard for coinage, based on the Indian rupee, weighing 11 g and minted in the three remaining regal mint stations in Isfahan, Tabriz, and Mashhad.

The amazing amount of gold and silver from the booty of Nader Shah’s campaigns to India finally formed the Qajar royal treasury and initially was minted to coins of one, two and five ashrafis, copying the old Safavid standard. Then Agha Mohammad Shah (r. 1785-1797), founder of the Qajar dynasty, replaced the

ashrafi with the tuman, though only quarter- and half-tuman coins were produced for circulation. The denomination of a tuman à ten silver coins of 5 g was the

hezar (lit. “1,000”), having a value of 1,000 dinars. Smaller denominations of half, quarter and one-seventh of a hezar, were thin silver coins of ten, five and one unit known as shahi-ye sefid, or white shahi, to distinguish them from the copper

shahis of 50 dinars. The copper coins were generically known as folus and ordinarily were struck at each mint in generally similar types in denomination of 5, 10 and 20 dinars. The principal denomination was the new founded monetary unit of rial à 1,250 dinars (one-eighth tuman = 25 shahis) which weighed about 12.67 g. The term rial had nothing to do with the Spanish or Latino-American currency named real but was an indigene Persian term, occurred in the late 18th century.

Agha Mohammad Shah’s wars and Fath Ali Shah’s splendid holding of court created enormous costs to the royal treasury. The continued decline of the price of silver caused a lightening of the tuman, which suffered further devaluation, and reducing the size of the actual coins became necessary. Thus, Fath Ali Shah changed the standard from a rial of 1,250 dinars, based on a silver tuman of 18 mesqals (= 83 g), to a tuman of 16 mesqals (= 73.6 g) à 10 hezars à 10 shahis. This standard became the common monetary system throughout the whole Qajar state. In 1826 the monetary unit of hezar became known by the people as saheb-qeran or simply qeran (usually rendered kran in European accounts). The name was derived from Fath Ali Shah’s title Saheb-Qeran (lit. “Keeper of the Fortunate Conjunction”, i.e. “Ruler over 50 lunar years”) used in the royal inscription after the thirtieth year of the monarch’s reign. The qeran was supplemented by smaller numbers of half- and quarter-qerans, remained the principal denomination until the end of the hammered coinage and became the silver rial of same value in Pahlawi time.

II. The Mint

Since antiquity in Persia the coinage prerogative, this is the regal law to establish the coinage standard, was a right of the central government. This included setting the currency, the right of minting, and the demand for any mint account. Hereby the financial proceeds were the most important part of prerogative. The regal administration also was in charge of engineering and running the mint stations, raising the coinage standard and minting the coins. The coinage standard says which kind and amount of precious metal (gold, silver), should be minted in which amount of coins of a certain nominal value.

The wealth of a country depends on a good currency founded in its purity. A soon as two different standards of money, one pure the other impure, become available in a country, the people will keep the pure and deal with the impure, causing inflation. Thus, to secure the standard of coins and fixed value of money, the central government exercised a monopoly over minting and put it under one single fiscal administration. Thus, one of the most important Persian administrative departments (divan-khaneh) from the Safavids to the Qajars was the treasury (sanduq-khaneh), under the control of the ministry of finance (wezarat-e maliyeh). This governmental branch was divided into the two sections of royal state treasury (khezaneh-ye mobarak-e maliyeh) or at least private royal treasury (khezaneh-ye khasseh) including the bullion, gems, jewellery and crown jewels (jawaherat-e saltanati), and the department of revenues and taxes (divan-e estifa), including the custodianship of the mint (amini-ye zarrab-khaneh).

Until the end of the Safavids there was no central mint in Iran; each region minted its own currency. So, in fact minting was a regal law but the prerogative of the provinces shifted to the local governors. Mint farming, the practice of subcontracting the production of coins to private individuals, with whom the profits were shared was very common. And, in theory, it was a rational system for securing reliable production facilities for coinage. But the removal of state supervision opened up avenues for abuse, for example, lowering the fineness of silver. So, the shahs did little to manage the currency, leaving to market forces the determination of the relationships between coins and the silver-gold ratio. Thus, anyone could bring gold or silver to the mint and have it refined and coined, for a fee. The services of the mints were thus available to everybody and not restricted to the state, which did, of course, profit handsomely from the mint establishments.

A big problem the central government had to deal with was devaluation. With a deflation of the coinage standard, money was made and the expenses of the state were paid by the rulers with reducing the standard of the nominal amount. This deflation often ran quietly over decades. Coins with a true market value to their nominal value were collected, melted down or cut in order to strike new coins with an extra benefit of copper to this newly gained metal.

The reason for the systematically devaluation up from the middle of the 18th century was the devaluation of silver and a rising need for money. The monetary basis of most of the countries like Iran at that time was silver. With the discovering of silver mines in America the price of silver versus gold broke down. In Iran a generically growth of population in the cities caused by migration into cities and the economical productivity and production remaining static, created an increasing need for food and caused finally inflation. Sometimes devaluations of the currency even were handled by the central government to serve the purpose of raising revenue for the private royal household or short-term emergencies like wars. After years of war and an expensive court, the state needed money. To pay all the costs the central government tried to make new money with a false value to its nominal to run business.

With the reign of the Qajars the first steps for technical improvements in minting were taken. Gold and silver were both used for currency and the balance between both metals was maintained. The mints did exchange pure gold and silver for ready-make currency of the same weight. The ten percent copper or brass that was added to the coins was sufficient to cover the expenses of the operation of the mint as well as subsidized the worn out coins. But the shah did not ask for any revenue from the different mints. At the Tabriz and Isfahan mints well-executed silver and gold coins bearing the ruler’s titles, mint name, date and value were struck along with the normal, less carefully minted products. From 1842 gold tumans and silver half-, single, and double-qerans were struck at the Tehran mint, remarkably uniform in type, with the royal inscription and a lion-and-sun motif as regal state symbol on the obverse and the mint and date, usually inscribed within an ornamental cartouche, on the reverse. Each mint had its own reverse designs and a distinctive style and ornamentation for the obverse. The mint name was often given a distinguishing epithet, for example, Dar os-Saltanat for Isfahan, Dar ol-Khelafeh for Tehran, Dar ol-Elm for Shiraz, Dar os-Sorur for Borujerd, Arz-e Aqdas for Mashhad, etc. In addition to these cities came the mint stations of Yazd, Kashan, Astarabad, Hamadan, Tabriz and Rasht. These types of coinage remained essentially the same until the Islamic Revolution of 1979.

III. The Master of the Mint

The imperial mint in Qajar time although privately operated in each city, was closely supervised by the government and under the jurisdiction of the treasurer (khezanehdar). It was his duty to look after the balance between the currency’s market value and the true value, and if necessary to collect the worn coins and make new coins. Thus, a person in charge of minting the gold from the royal treasury into coins had been appointed. The precise functioning of the mint was headed by the mint master (zarrab-bashi). He was a state official who headed the master smith, the dye-cutter and the minter in running the local mint station, minted the coins, and held the mint metal. For his service he got a part of the benefits from minting next to some privileges and rights. Sometimes dynasties of mint masters occurred, being in governmental service for generations. Finally the post of a chief master of the mint, called warden of the mint or imperial assayer (moayyer ol-mamalek) was created as an officer without any profit-sharing, but with a certain salary. It was the responsibility of this new office to supervise the mint masters and to assure the quality and equivalency, the correct size and weight of all the gold coins. The moayyer ol-mamalek was in charge of controlling the mintage according to fiscal regulations of the right metal alloy. Whenever counterfeits or impurity were discovered in coins, the faulty ones were collected and melted down and new ones were issued in their place, providing full value. The cost of a new mintage was subsidized by him, as well. He regulated the various offices of the mints, the assessment of minting and fees, was custodian for the coinage tools and bookkeeper for the different weight units in the central accounting system.

Up from the time of Nader Shah Afshar, the position of treasurer and overseer of all mints was traditionally the property of the Moayyeri Family, the family of Moayyer ol-Mamalek.

IV. Chronicle of the Moayyeri Family

1. Hossein Ali Beyg Bastami “Moayyer ol-Mamalek”

Founder of the Moayyeri Family and the first Imperial Assayer was Hossein Ali Beyg (sometimes called Hassan Ali Beyg) Bastami “Moayyer ol-Mamalek”. He was a descendant of the famous Abu Yazid Teyfur ben Issa ben Suroshan al-Bastami, called Soltan Bayazid Bastami (777-874), a medieval Islamic Sufi-mystic of Persian origin from Bastam, a town in the Qumes district next to Shahrud in the province of Semnan.

Initially being a professional locksmith (chalingari), Hossein Ali entered royal service of the last Safavid ruler Shah Soltan Hossein (r. 1694-1722) and then of the latter’s son and pretender to the throne Tahmasb II (r. 1722-1732), became assayer (moayyer) and an important Safavid official. In 1726 Tahmasb II dispatched him to report on the activities of the ambitious troop commander

Nader Qoli Beyg (later called Nader Shah Afshar), who fought against the Afghan invaders and was then campaigning around Abivard in Khorassan. Hossein Ali convinced Nader to join Tahmasb in crushing the rebel Malek Mahmoud of Sistan and appointed him deputy governor of Abivard on Tahmasb’s behalf. This encounter marked the beginning of a long and close connection between Hossein

Ali and Nader, who then called himself in honour of the Safavid prince Tahmasb Qoli Khan (lit. “Slave of Tahmasb”). In the early 1730's, Hossein Ali resided in Isfahan, carrying messages and gifts between Nader and Tahmasb as well as overseeing fiscal affairs there. He kept Nader informed about the situation of the royal court, and played a part in Tahmasb’s deposition and the crowning of the infant Shah Abbas III in 1732. By 1736, Hossein Ali attended the Moghan coronation ceremony where Nader was crowned to Nader Shah Afshar (r. 1736-1747). After that he got the post of Lord Assayer (moayyer-beyg), became one of Nader’s principal advisors and vizier (wazir), and headed several diplomatic missions with the Ottoman Empire, also attending the shah's campaign to India. From that time until Nader’s death, Hossein Ali Beyg resided permanently in the shah’s camp. When Nader was assassinated in 1747 with two of his closest ministers by Afshar and Qajar emirs, Hossein Ali Beyg escaped alive, causing Nader’s Jesuit doctor, Bazin, to believe that he had some involvement in the plot.

After Nader’s overthrow Hossein Ali Beyg served for a short time as advisor to Adel Shah Afshar (r. 1747-1748), Nader’s nephew and successor. After the latter was deposed, he then made his way back to Isfahan, where he counselled Karim Khan Zand (r. 1750-1779) to enthrone Abu Torab Mirza as Shah Esmail Safavi III in 1750 and was made Cief Assayer (moayyer-bashi) of the Zand domains.

Finally he joined the service of Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar (r. 1779-97) the future Shah of Persia and got the title (laqab) of “Moayyer ol-Mamalek” (lit. "Assayer of the Realm"). Hossein Ali Beyg Bastami “Moayyer ol-Mamalek” issued two sons: Agha Musa and Dust Ali Khan Bastami “Moayyer ol-Mamalek”.

1.1. Agha Musa (d. 1814)

Agha Musa was the elder son of Hossein Ali Beyg Bastami “Moayyer ol-Mamalek” and 1789-1797 during the reign of Agha Mohammad Shah Qajar one of the shah’s tax accountants (mostowfī) at court. After falling out of favour and being punished by the ruler, he retired to Kerbala in Iraq where he died in 1814, having issued one son: Mirza Abbas Forughi Bastami.

Agha Musa was the elder son of Hossein Ali Beyg Bastami “Moayyer ol-Mamalek” and 1789-1797 during the reign of Agha Mohammad Shah Qajar one of the shah’s tax accountants (mostowfī) at court. After falling out of favour and being punished by the ruler, he retired to Kerbala in Iraq where he died in 1814, having issued one son: Mirza Abbas Forughi Bastami.

1.1.1. Mirza Abbas Forughi Bastami (1798-1857)

Mirza Abbas Forughi Bastami was born 1798, the son of Agha Musa and grandson of Hossein Ali Beyg Bastami “Moayyer ol-Mamalek”, and became a well-known Persian 19th century poet. He received little formal education in his childhood and only later on acquainted himself with the literary knowledge of his time. In 1814 the sixteen-year-old Abbas returned to Iran and for the next few years lived in Sari in the province of Mazandaran, with his uncle Dust Ali Khan “Moayyer ol-Mamalek”, the second overseer of the imperial mint. In his early twenties Abbas was also introduced to the court of Fath Ali Shah (r. 1797-1834) by that Dust Ali Khan. A few years later, the shah sent him to Mashhad to join the entourage of Prince Hassan Ali Mirza “Shoja os-Saltaneh”, the shah’s 6th son and governor of the province of Khorassan. At his court Abbas changed his pen name (tajjalos) from Meskin to Forughi (lit. "Bright"), in honour of the prince’s second son Forugh od-Dowleh (lit. "Brightness of the State"). Upon the death of Fath Ali Shah in 1834 Mirza Abbas Forughi returned to Tehran, where he lived most of his life, though during the reign of Mohammad Shah (r. 1834–48) he spent several years near the holy shrines in Iraq, drawn there by his strong inclination to mysticism. In 1857 Mirza Abbas Forughi Bastami died in Tehran and the very same year his poetry selection or divan, containing 321 gasals or double-rhymes of about eleven lines each in the lyrical style of famous Saadi, was published by Assadollah Mirza Qajar.

Mirza Abbas Forughi Bastami was born 1798, the son of Agha Musa and grandson of Hossein Ali Beyg Bastami “Moayyer ol-Mamalek”, and became a well-known Persian 19th century poet. He received little formal education in his childhood and only later on acquainted himself with the literary knowledge of his time. In 1814 the sixteen-year-old Abbas returned to Iran and for the next few years lived in Sari in the province of Mazandaran, with his uncle Dust Ali Khan “Moayyer ol-Mamalek”, the second overseer of the imperial mint. In his early twenties Abbas was also introduced to the court of Fath Ali Shah (r. 1797-1834) by that Dust Ali Khan. A few years later, the shah sent him to Mashhad to join the entourage of Prince Hassan Ali Mirza “Shoja os-Saltaneh”, the shah’s 6th son and governor of the province of Khorassan. At his court Abbas changed his pen name (tajjalos) from Meskin to Forughi (lit. "Bright"), in honour of the prince’s second son Forugh od-Dowleh (lit. "Brightness of the State"). Upon the death of Fath Ali Shah in 1834 Mirza Abbas Forughi returned to Tehran, where he lived most of his life, though during the reign of Mohammad Shah (r. 1834–48) he spent several years near the holy shrines in Iraq, drawn there by his strong inclination to mysticism. In 1857 Mirza Abbas Forughi Bastami died in Tehran and the very same year his poetry selection or divan, containing 321 gasals or double-rhymes of about eleven lines each in the lyrical style of famous Saadi, was published by Assadollah Mirza Qajar.

1.2. Dust Ali Khan Bastami “Moayyer ol-Mamalek” (d. 1821) Dust Ali Khan Bastami “Moayyer ol-Mamalek” was the younger son of Hossein Ali Beyg Bastami “Moayyer ol-Mamalek”, born in Isfahan around 1760. Under Agha Mohammad Shah he inherited his father’s posts and titles and firstly became 1797 private chamberlain (pish-khedmat-e khass) to the shah and the family's second Moayyer ol-Mamalek and treasurer (khazanehdar). Under Fath Ali Shah he was one of the most important Qajar dignitaries and held the offices of chamberlain (pish-khedmat), trustee of the treasury (amin-e khazineh), custodian of the royal private jewel case (vaqef-e dafineh-ye shahi) and bookkeeper of the whole empire’s financial affairs (saheb-e jam-e tamam-e vojuhat-e mamalek-e mahruseh). Several years he resided in Sari in the province of Mazandaran. In 1821 Dust Ali Khan Bastami “Moayyer ol-Mamalek” died of cholera on the way from Hamadan to Kermanshah at the town of Kengavar, when he accompanied Fath Ali Shah on his campaign to Iraq. His first house in the ark district of Tehran contained five courtyards, two baths and a small and a large stable. The family moved then to a Perso-European styled luxurious mansion called "Reshk-e Behesht" in Bagh-e Ferdows (lit. “Paradise Garden”) at Tajdrish in Tehran’s north, outside the city limits.

Dust Ali Khan Bastami “Moayyer ol-Mamalek” had several children by his wife Khajiyeh Khanom, including Hossein Ali Khan “Moayyer ol-Mamalek” (the father of the further Moayyeri Family, Mohammad Qassem Khan Wali (the father of the Wali Family) and Mohammad Hossein Khan Bastami (the grandfather of the further Zarrinnaal and Zarrinkafsch Family).

1.2.1. Hossein Ali Khan “Moayyer ol-Mamalek” (1798-1857)

Hossein Ali Khan “Moayyer ol-Mamalek” was the eldest son of Dust Ali Khan Bastami “Moayyer ol-Mamalek” by Khajiyeh Khanom and grandson of Hossein Ali Beyg Bastami “Moayyer ol-Mamalek”. After his father’s death he inherited the titles and offices and in 1822 became imperial assayer, treasurer and director of the imperial mint (rais-e zarbkhaneh), according to his new rang of saheb-ekhtiyar (lit. “Master of Full Power”). He was married to his cousin Shirin Shah Khanom, by whom his only son Dust Ali Khan II was born in 1821. After his first wife's death, in 1833 he married Princess Farzaneh Khanom, 39th daughter of Fath Ali Shah by his 44th wife Moshtari Baji from Shiraz. Because of his father’s good reputation, Hossein Ali Khan did not need to pay the necessary bride price to the shah. The marriage was celebrated with the greatest oriental pomp and the bride joined her husband's house on an elephant! When their marriage still remained childless they were divorced and Hossein Ali Khan married in 1834 her sister Princess Pasha Khanom, 38th daughter of Fath Ali Shah by Moshtari Baji, by whom he had a daughter, Mehr-e Jahan Khanom. Under the reign of Mohammad Shah (r. 1834-1848) Hossein Ali Khan continued his duties and got the governorship of the province of Yazd. First, his brother Mohammad Qassem Khan Wali was deputy

(nayeb) in charge of the provincial administration, and then succeeded by Hossein

Ali Khan's own son Dust Ali Khan II. In 1838 Hossein Ali Khan took part in the shah’s Herat campaign as an army inspector (nazer). Also during the reign of Nasser od-Din Shah (r. 1848-1896) Hossein Ali Khan stayed in office, and in 1852 he became head of the “Centre of Art and Craftsmanship” (majmaol-dar os-sanaye) founded by Grand Vizier Amir Kabir. There he supervised the illustration of Abol Hassan Ghaffari’s copy of Thousand and One Nights (alf leyla wa leyla), one of the most ambitious art projects of that time. In 1857 Hossein Ali Khan “Moayyer ol-Mamalek” died at Tehran and was buried at Kerbala in Iraq.

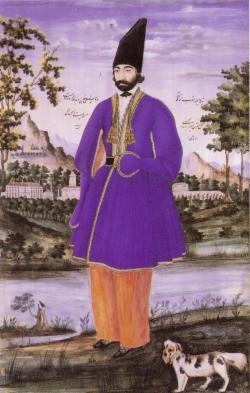

1.2.1.1. Dust Ali Khan “Moayyer ol-Mamalek” (1821-1873)

Dust Ali Khan (II) “Moayyer ol-Mamalek” was the only son of Hossein Ali Khan “Moayyer ol-Mamalek” by his cousin Shirin Shah Khanom. Born in 1821 at Tehran, he was during Mohammad Shah’s reign until 1848 his father’s deputy for Yazd. In 1848 he was made at his father’s intercession private chamberlain to the shah and in 1857 after his father’s death, Dust Ali Khan II got the post and office of treasurer and the title of “Moayyer ol-Mamalek” as well as the supervision over the cannon arsenal (zamburak-khaneh) and royal residence (takht-khaneh) and the administration of all court businesses (boyutat). In 1866 the custody of the coach house (kalishkeh-khaneh) as well as the administration of the provinces of Marw, Gilan and again Yazd was added to these posts. In 1871 he became member of the Privy Council (dar ol-showra-ye kobra), accompanied the shah on his tour to Kerbala, and received the “Decoration of the Most August Portrait” (neshan-e temsal-e homayun), the rank and sash (hamayel) of an Amir-e Tuman (lit. “Commander of 10,000”, i.e. Major-General) and the title of “Nezam od-Dowleh” (lit. “Order of the State”). In Tehran Dust Ali Khan II built a religious school (madreseh), the famous palace of Shams ol-Emareh at the Golestan palace complex and the theatre of Takiyeh-ye Dowlat. On April 17 1873 Dust Ali Khan “Moayyer ol-Mamalek” “Nezam od-Dowleh” died at Tehran. With his wife Mah-e Nessa Khanom, called Begom Nessa (d. 1875), he issued four children: (Amir) Dust Mohammad Khan “Moayyer ol-Mamalek”, Noor Mohammad Khan, Zahra Khanom and Fatemeh Khanom.

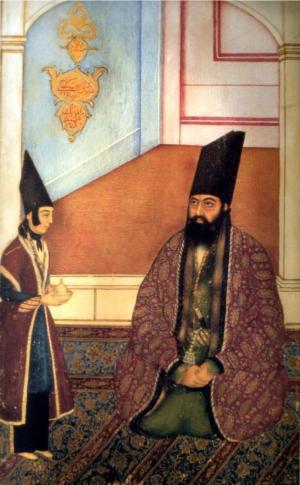

1.2.1.1.1. Dust Mohammad Khan “Moayyer ol-Mamalek” (1856-1912) Dust Mohammad Khan (sometimes also called Amir Dust Mohammad Khan) “Moayyer ol-Mamalek” was born 1856 and the eldest son of Dust Ali Khan (II) “Moayyer ol-Mamalek” by Mah-e Nessa Khanom. Already in 1866, at the age of ten, he was married to Princess Fatemeh Khanom “Esmat od-Dowleh” (b. 1854, d. 1905), 3rd daughter of Nasser od-Din Shah by his 3rd permanent wife (zan-e

aqdi) Princess Khojasteh Khanom “Taj od-Dowleh” (daughter of Seyfollah Miza, 42nd son of Fath Ali Shah). In 1869 he took over his father’s post and title of “Moayyer ol-Mamalek”, and in 1873 after his father’s death the governorship of Yazd and Gilan. In 1875, after his mother’s death (who in fact carried out all duties for her son), he retired from all official posts and court life, travelled to Kerbala and in 1882 further on to Europe, where he stayed most of his time in Paris until 1885. After his return he only looked after bird breeding and farming. In 1912 Dust Mohammad Khan “Moayyer ol-Mamalek” died on a trip in Odessa. By his wife Fatemeh Khanom “Esmat od-Dowleh” he issued four children: Dust Ali Khan (III) “Moayyer ol-Mamalek” aka Mr Dust Ali Moayyeri (b. 25/06/1876, d. 15/11/1966), Fakhr ol-Taj, Dust Mohammad Khan II and Esmat ol-Molk.

Dust Mohammad Khan was the family’s last real treasurer. After the death of his father, having been raised too much like a rich spoiled child, along with being Nasser od-Din Shah’s son-in-law, he was too proud to accept the advice of the elder courtiers. Thus, the shah’s chief butler Agha Ebrahim “Abdar-bashi”, called “Amin os-Soltan” (lit. “Confidant of the Monarch”), was encouraged to rival him and through this connection the courtiers were able to get access to the treasury. The duties of treasurer were accumulate in the single hand of ambitous Amin os-Soltan, those of an overseer over the mint shifted to his ally Hajji Mohammad Hassan “Amin ol-Zarb” (lit. “Confidant of the Mint”), and Dust Mohammad Khan

became now only "Moayyer" in name. Amin ol-Zarb, a successful Iranian

entrepreneur, in 1875 imported a minting machine from Europe supervised by the

Austrian instructor Franz Pechan von Praegenberg. With the modernisation of

coinage the local mints were closed and the hammered coinage was replaced by

machine-struck versions in all denominations. But this was also the beginning of making money for both, Amin os-Soltan and Amin ol-Zarb as well as of monetary

devaluation in Iran in the second half of the 19th century. With the new silver mines discovered in America a total imbalance of between silver and gold was caused, the fixed price of silver decreased as opposed to the value of gold and foreign currency, and the qeran did not have the same buying power as before. The current gold coins were collected, and silver, which was already devalued, became the monetary basis of the currency of Iran and started the country’s economical crisis that lasted until the end of World War II.

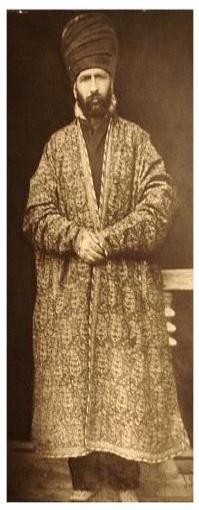

Hossein Ali with his son Dust Ali Khan "Moayyer ol-Mamalek", 1852.

Dust Ali Khan (II) “Moayyer ol-Mamalek”, Esmat od-Dowleh and Mah-e Nessa Khanom, Dust

Mohammad Khan “Moayyer ol-Mamalek”.

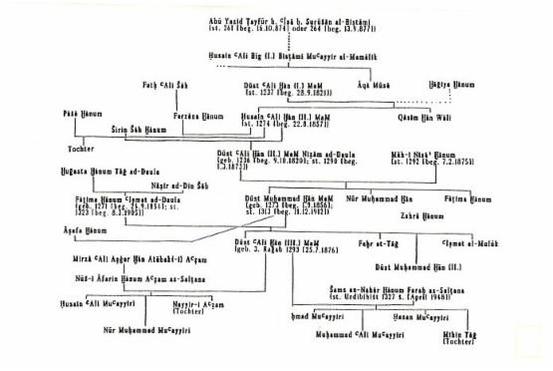

Sheme of the family tree of Moayyer ol-Mamalek.

The Moayyeri town residence in Tehran: The main building with two side wings around the great pool in the court yard.

The Moayyeri town residence in Tehran: View back to the entrance gate and the right wing.

1.2.2. Mohammad Qassem Khan Wali (1805-1872)

Mohammad Qassem Khan Wali was the second son of Dust Ali Khan (I) Bastami “Moayyer ol-Mamalek” by Khajiyeh Khanom and grandson of Hossein Ali Beyg Bastami “Moayyer ol-Mamalek”. He was the father of the Wali Family. For their family history see: The Wali Ancestors.

Mohammad Qassem Khan Wali was the second son of Dust Ali Khan (I) Bastami “Moayyer ol-Mamalek” by Khajiyeh Khanom and grandson of Hossein Ali Beyg Bastami “Moayyer ol-Mamalek”. He was the father of the Wali Family. For their family history see: The Wali Ancestors.

1.2.3. Mohammad Hossein Khan Bastami “Mir Panj” (1810-1868)

Mohammad Hossein Khan Bastami “Mir Panj” (lit. "Master of a Division of Five", i.e. Brigardier-General") was the third son of Dust Ali Khan (I) Bastami “Moayyer ol-Mamalek” by Khajiyeh Khanom and grandson of Hossein Ali Beyg Bastami “Moayyer ol-Mamalek”. Born probably around 1810 and died young, during the reign of Nasser od-Din Shah he was troop commander (farmandeh), headed his own military division with the rank of a general and led some local military campaigns for the shah, especially to Yerevan at the Georgian border territory.

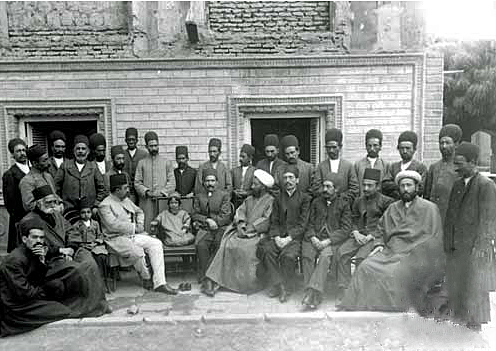

Mohammad Hossein Khan Bastami married Effat od-Dowleh, sometimes also called Assiyeh Khanom, a lady of the royal harem. Because Nasser od-Din Shah himself took care about her welfare, and even supervised the later marriage of her eldest daughter, called Pari Soltan Khanom (lit. "Faerie of the Monarch"), probably this lady could be the shah’s own younger half-sister, Princess Effat od-Dowleh Khanom Qajar, the 7th daughter of the late Mohammad Shah by Bolour Khanom Zandiyeh. By her Mohammad Hossein Khan Bastami had issued two daughters: Pari Soltan Khanom Pir-Bastami (b. ca 1853), and a second daughter, born in Georgia, who was married to the shah’s courtier Mirza Yusouf Khan "Sana' ol-Molk", orifinally from Georgia too. By him that second daughter had issued also a daughter: Effat ol-Molk Sana'i, who married her distant cousin, Mirza Ali Asghar Khan aka H.E. Ali Asghar Zarrinkafsh, the younger son of Pari Soltan Khanom Pir-Bastami and Agha Mirza Zaman Khan Kordestani “Lashkar-newis”.

In 1867 Pari Soltan Khanom Pir-Bastami, was married to Agha Mirza Zaman Khan Kordestani “Lashkar-newis” the son of Oghli Beyg "Monshi ol-Molk" of the Zarrinkafsh Clan from Sehna, who wanted a familiar connection to a leading Qajar bureaucratic family of noble blood and an attempt for another unification with the Qajar dynasty itself. It is told within the family that at first the bride's parents did not want to give Mirza Zaman Khan their daughter's hand until they were convinced of the Kurdish groom's wealth. So, sending the necessary gifts of the ring, earrings, cashmere shawls, wedding sweets and cakes with the marriage contract, Mirza Zaman Khan came to the marriage ceremony at Mohammad Hossein Khan's house riding a horse with golden horseshoes to pick up his bride. - A tradition once already happened in his line and causing the very special last name "Zarrinnaal" of his family! Finally the shah even intervened and agreed to that marital bond and this is why his niece Pari Soltan Khanom sometimes was nicknamed "Zarrin Khanom" (lit. "Golden Lady") after her marriage. Becoming the matriarch of our entire family she gave birth to three children by Agha Mirza Zaman Khan, two sons and one daughter: Agha Mirza Ali Akbar Khan-e Zarrinnaal "Lashkar-newis" "Nasr-e Lashkar", Mirza Ali Asghar Khan aka H.E. Mr Ali Asghar Zarrinkafsh and Banou Fatemeh Soltan Khanom aka Mrs Fatemeh Afshartous. All three children were married with close relatives from their mother's side and members of the Qajar aristocracy and became the founders of the three family main lines Zarrinnaal (which includes the Zarrinkafsch-Bahman), Zarrinkafsh

and Afshartous.

Princess Effat od-Dowleh Khanom Qajar and her daughter Pari Soltan Khanom Pir-Bastami.

Pari Soltan Khanom's sister and the latter's daughter Effat ol-Molk Zarrinkafsh née Sana'i.

Ancestry line:

Hosseyn Ali Beyg Bastami “Moayyer ol-Mamalek”> Dust Ali Khan “Moayyer ol-Mamalek” > Mohammad Hosseyn Khan “Sepahdar” > Pari Soltan Khanom Pir-Bastami > Agha Mirza Ali Akbar Khan-e Zarrinnaal “Lashkar-newis” “Nasr-e Lashkar” > Kazem Khan Zarrinkafsch > The House of Zarrinkafsch (Bahman-Qajar)

Sources:

Charyar Adle: “Bestām”, in: Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. IV, London and New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1990, p. 177-180.

Stephen Album/ Michael L. Bates/ Willem Floor: “Coins and Coinage”, in:

Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. VI, edit. by Ehsan Yarshater, Costa Mesa: Mazda Publishers, 1993, p. 14-41.

Alī Khan Wālī: The Photograph Collection of the Golestan Palace: The Album of Photographs by Ali Khan Vali. Qajar, edit. by Jeff Spurr, Boston: Research Department of Harvard University, 2006, Internet: September 2008, http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:FHCL:1125271.

Peter Avery: “Nādir Shah and the Afsharid Legacy”, in: Cambridge History of

Iran, Vol. 7: From Nadir Shah to the Islamic Republic, edit. by Peter Avery, Gavin Hambly and Charles Melville, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991, p. 3-63.

Mehdī Bāmdād: Šarh-e hāl-e reğāl-e Īrān dar qorūn-e 12 wa 13 wa 14, 6 vols, Tehran: Ketābforūšī-ye Zawwār, 5th edit., 1378 H.š. [1999]; vol. I, p. 433-434; idem p. 495-501; vol. VI, p. 90-95.

Ferydoun Barjesteh: “The Fath Ali Shah Project”, in: Journal of the International Qajar Studies Association, Vol. IV, Rotterdam: Barjesteh van Waalwijk van Doorn, 2004, S. 191

Gerhard Böwering: “Bestāmī, Bāyazīd”, in: Encydlopaedia Iranica, Vol. IV, edit. by Ehsan Yarshater, London and New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1990, p. 183-186.

Heshmad Moayyad: “Forūġī, Bestāmī”, in: Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. VIII, edit. by Ehsan Yarshater, Costa Mesa: Mazda Publishers, 1998.

Dūst ‘Alī Mo‘ayyerī: Reğāl-e ‘asr-e nāsserī, Tehran: Nashr-e tārīkh-e Īrān. Majmū‘a-ye motūn wa esnād-e tārīkhī. Ketāb-e dahom (Qāğār), 1958, p. 83.

‘Abdollāh Mostowfī: Šarh-e zendegānī-ye man, yā tārīkh-e ejtemā‘ī wa edārī-ye dowreh-ye Qājār, Tehran 1326 (1947), transl. and edit. by Nayer Mostofi-Glenn, The Administrative and Social History of the Qajar Period [The Story of my Life], Costa Mesa: Mazda Publishers, 1997, p. 222.

Klaus Dieter Streicher: Die Männer der Ära Nāsir: Die Erinnerungen des Dūst

‘Alī Hān Mu‘ayyir al-Mamālik, Frankfurt am Main: Verlag Peter Lang, 1989 [Heidelberger Orientalische Studien, Band 12], p. 20 ff.

Ernst Tucker: “Hasan-‘Alī Beg Bestāmī”, in: Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. XII, edit. by Ehsan Yarshater, New York: Encyclopaedia Iranica Foundation, 2004, p. 40-41.

Interview with Mrs Victoria Zarrinkafsh, Tehran, 2005.

This website was created by Arian K. Zarrinkafsch (Bahman-Qajar).