| The Heroic and Historic Era The Kurdish Era The Qajar Era The Pahlawi Era | The Zarrinkafsch-Bahman (Qajar) Family |

After

fifty years of civil war, following the Safavid downfall and Nader

Shah's murder, in 1796 Agha Mohammad Shah (r. 1785-1797), chief of the

Quvanlu branch of the Qajar tribe and ruler in northern Persia, could

unify all Persian territories, crowned himself shah-an-shah

(lit. "King of Kings", i.e. Emperor) of Persia and founded the new Qajar

dynasty, which lasted seven generations until 1925. His nephew and

successor Fath Ali Shah (r. 1797-1834) consolidated the

dynasty's power, especially by marital bonds to Persian aristocratic

families, and created a splendid court. But also, in two Perso-Russian

wars he lost the Transcaucasian provinces to the Russian Tsar. His son

and crown prince Abbas

Mirza "Nayeb os-Saltaneh", the viceroy and governor of Azerbaijan,

spent most of his life on battlefields and modernized his province but

died already as young man by kidney disease when in a battle against Turkoman rebels in 1833.

Abbas Mirza's eldest son became Fath Ali Shah's successor to the Qajar

throne as Mohammad Shah (r. 1834-1848), a quiet man without the

luxurious attitude of his grandfather. When he died of gout in 1848 his

eldest surviving son Nasser od-Din Shah (r. 1848-1896) succeeded him,

one of the most prominent Qajar monarchs. During his nearly fifty years

of reign reforms and modernization in social, economic and technical

sectors took place when Persia entered the "Great Game" between Russia

and Great Britain and the shah tried to balance the two superpowers'

influence in his own country. Nasser od-Din Shah with his

ministers planned to centralize the bureaucratic structures and wanted

to reform the army. Thus, in this time one of our family's immediate

ancestors, my great-great-grandfather, left his homeland in Kurdistan

and made his way to Tehran starting a career as a high official at the

Qajar imperial court of Golestan Palace.

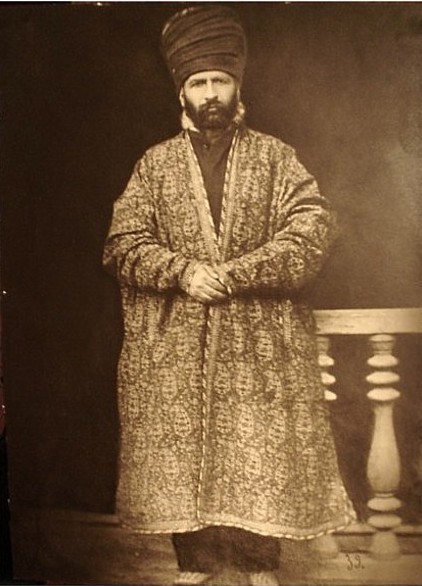

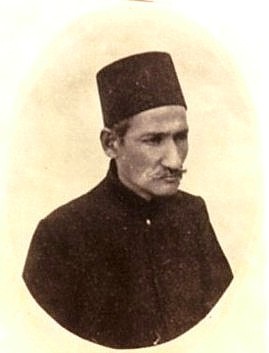

11. Agha Mirza Zaman Khan Kordestani "Lashkar-newis" (1840-1906)

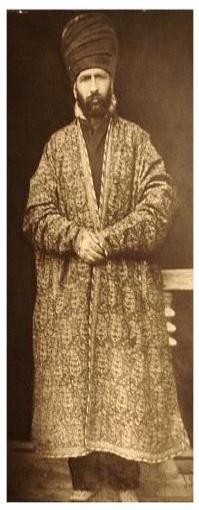

Agha Mirza Zaman Khan Kordestani "Lashkar-newis". He is shown as court official with royal robe of honour and this clan-typical black Kurdish klut (turban) in Zand style, Tehran ca. 1880.

Oghli Beyg's son Agha Mirza Zaman Khan Kordestani "Lashkar-newis" was born in Sanandaj at the Khusrowabad

residential palace around the year 1840 and died at Tehran after 1905.

After an extensive education in Arabic, literature, calligraphy and

arithmetic, he left Sanandaj after Nasser od-Din Shah Qajar terminated

the Ardalan rule in Kurdistan by deposing the last wali

and removing him with his own candidate. Himself from a family of court

grandees in Sanandaj, related to the shah, and responsible for army supplyment, on 1rst of July 1859 young Master Zaman joined the

shah's camp when Nasser od-Din Shah visited with his entourage

Kurdistan on a royal tour and stayed in its capital town of Sanandaj for three days. He entered the royal tent, paid obedience to the shah and offered his service. Because

the wali of Kurdistan was not able to satisfied the wishes of the

shah's retinue and several of them were getting angry, the court

departed from Kurdestan taking young Zaman with it. Via Tabriz and

Maragheh he then moved to Tehran and reached the capital on 19th of

October 1859. Some

samples of his handwriting convinced Zaman's superior at court to give him an

employment at the imperial court offices and so he became a

bureaucrat in the governmental administration. His career started there as a clerk (mirza) with a beginning salary of five to six tuman per

month (400-480 US Dollar gold!), the double income of a court servant,

and he was in charge of fiscal duties of the government, administration

and military, responsible for the province of Kurdistan in special.

After der Ardalan rulers were replaced by the shah with the later's

uncle Prince Farhad Mirza "Mo'tamad od-Dowleh" as governor of Kurdistan

in 1867, Mirza Zaman settled permanently in Tehran and moved from the Ark district to that of

Oudlajan

in the north-eastern part where the nobility had its residences and he

founded a family. Then, in 1872 with the improvements of Mirza Hossein

Khan "Moshir od-Dowleh" Mirza Zaman worked for the Ministery of War,

and finally got the post of lashkar-newis (lit. "Army Scribe", i.e. Muster-Master), who was chief paymaster

of the troops and head of military administration. Until 1904 he worked

in this office under Prince Vajihollah Mirza "Seyf ol-Molk" as minister

of war and this office became the hereditary post in his family for three generations.

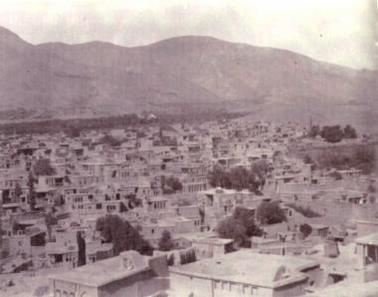

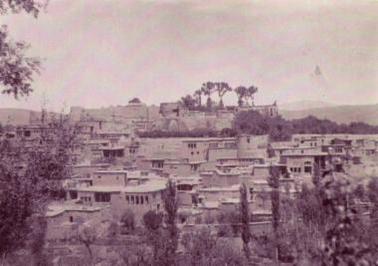

View of old Sanandaj with the city centre round the peak Teppeh-ye

Painshahr (also Teppeh-ye Tus-Nowzar) topped by the wali's fortress.

The Office of Lashkar-newis – Muster-Master of the Royal Troops

From the very beginning the Qajar central government was divided into an administrative part (divan) and the army (lashkar), both housed in the citadel (arg) of Tehran. Therefore, the ministry of army (wezarat-e lashkar), later ministry of war (wezarat-e jang) needed an own administration. After the reforms of army (nezam-e jadid, lit. “New Orderly Army”) introduced by Abbas Mirza in 1828, and continued by Nasser od-Din Shah during the second half of the 19th century, the government needed scribes, clerks and civil servants to write and copy lists about tax, salary, material stuff and recruiting. Head of all these clerks in army service was the Lashkar-newis (lit. “Army Scribe”). This governmental post did exist since Safavid time and based on the medieval Islamic official of Arez (from Arabic araza,

“to lay open to view,” i.e. inspection), who had charge of the

administrative side of the military forces, being especially concerned

with payment, recruitment, training, and inspection. The Lashkar-newis

was the chief muster-master of the royal troops, and as the army’s

paymaster-general, finally, he was head of the whole military

administration apparatus in Qajar time. Under Agha Mohammad Shah the Lashkar-newis became responsible for the recruitment, arrangement, logistics and supply of the whole army; he thus combined many of the duties of a modern war minister, paymaster-general, and quartermaster-general.

And finally, he became the central dignitary of military logistics; as

the army’s chief caterer and paymaster he was in charge for the salary

of every army member (asaker), which included not only military persons but court servants and provincial officials, too. Therefore, the Lashkar-newis

supervised a staff of recruitment clerks of seven scribes and

secretaries responsible for the exact accountancy of the troops’ supply

unit in men and feed. Also, it

was the muster-master of the area in question who set the system of

recruitment clerks under his jurisdiction and submitted an annual report

of all transactions of the army in his domain. The different recruitment officials were based in the emarat-e nezam (lit. “Edifice of Army”, i.e. military headquarter), and the rais-e daftar-e lashkar was chief of the provincial army secretariat, while the mostowfi-ye nezam was the revenue officer of the army.

The Persian army traditionally consisted of a tribal cavalry force (rekabi) and an infantry unit mostly made of militia volunteers (cherik),

which was recruited when it was necessary by the local governors. The

central government recruited soldiers for infantry and artillery (tofanghchi wa tupchi) from the provinces based on the amount of taxation from each area. This military tax (bonicheh-ye sarbaz)

was introduced as a replacement for the old system of tribal levies by

Prime Minister Mirza Taqi Khan "Amir Kabir" in about 1850, based on

earlier reforms of

Abbas Mirza, and legalized in the recruitment law (qanun-e sarbaziri) of 2 November 1915 by the Majles. Under the bonicheh-ye sarbaz

system each village, district, or tribe was required to provide a

number of recruits proportional to the amount of its revenue

assessment. As with the agricultural bonicheh

taxation system, set according to the fertility and running costs of

farmland, the base for calculation differed in different areas; it

could be amount of land under cultivation, available amount of water,

population, or number of animals owned by a tribal group.

Theoretically one recruit had to be provided for every unit of revenue,

which could range from 12 to 20 tumans.

The recruits only were taken from parts of Iran popular for the best

soldiers like Astarabad, Azerbaijan, Khorassan, Kurdistan, Mazanderan,

Qazvin, Sistan and Zarijan. The southern provinces of Fars and Kerman

often were added to these areas of military tax system. In order to

offset the resulting imbalance in the tax burden on different

provinces, the government reduced the level of cash revenues required

from those liable to bonicheh-ye sarbaz

and correspondingly increased them for those that were exempt. Land

owned by princes, great proprietors, notables, and religious leaders

was exempt from this taxation, as was that belonging to Christians,

Jews, and Zoroastrians, to whom different tax regulations were

applied. Also no land tax was levied in the towns, and their

inhabitants were exempt, as were peasants living on crown lands.

According to the law, one of every ten men in a village was to be taken for military service; he was supposed to be a padar (taxpayer), an owner of land or cattle. If a man from the same village who was not a padar

volunteered for military service, the community had to provide him with

funds for during his period of service. So, the army paid the soldier’s

way to the training camp (where he was drilled a couple of hours per

day) and his salary and fodder (hoquq o jireh),

during the six-month period in which he was under arms each year.

During the other six months he was supposed to be on half-payfrom the provincial budget, estimated on an annual basis, which was entered separately in the budget (dastar al-amal) of each province under the heading shesh-maha-ye mahall (“local six months’ salary tax”). With

this system the number of recruits needed from each province was

calculated by the clerks for the annual provincial budget.

The basic training was about a year and the recruited soldier had to be ready to serve about two to four years.

Soldiers in service enjoyed only the usufruct of their property; the

government held the property itself as security for military equipment

and to prevent desertions. In order to support the recruited soldier’s

family in his absence, either the village as a whole or the remaining

nine men of the base group had to pay an annual subvention, called khanwari (“home allowance”). The

khanwari

was either paid directly to the soldier’s family or collected by the

government, which was supposed to pass it on to the soldier. Its amount

was paid in kind or cash or a combination of both, and was apparently

fixed by the interested parties themselves

without interference from the authorities; it thus differed greatly

from area to area. In cities like Tehran and Tabriz it was 5 and 12

tumans; in provincial towns like Ardabil 1.5, Qazvin 3 and Urmiyeh 5 tumans; and in tribal districts like Khalkhal 1, Qaraghan 1.5, Shaqaqi 10 and Qaradaghi 16

tumans. In some parts of the country, when an infantry or artillery recruit had to join his regiment, the owner of his village (saheb-e bonicheh) or the local peasant proprietors (khorda mallek) had to give him or his family a bounty for support in his absence. It was known as komak-e kharj (“expense allowance”) or padarana

(“allowance”), the amount varying from 5 to 40 tumans in cash or kind. Although the khanwari was paid every year, the padarana was paid only once. Some regiments, however, including all cavalry regiments, did not have the right of khanwari, because they were funded and paid by their tribes, called only in case of war and did not receive money while on leave at home.

The bonicheh-ye sarbaz was

collected by a recruitment sergeant (often a large landed proprietor or

chief of the district), accompanied by several of his officers and a mostowfi,

touring the villages that were liable for recruits. The regulations

stipulated the religion, age, height, and health conditions of

prospective recruits. The village elders (rish-sefid)

would already have selected those ready for military service. The

sergeant would select from among them the most suitable, rejecting the

unfit. Richer families paid for exemption from military service.

Villages that could not deliver their assessed quotas were in practice

reduced to levels reflecting their economic situation. Finally the

taxation results were given to the government officials and the

muster-master in charge of that region checked all the revenues. Like

the alphabetical taxation list he had a master list with all recruits

and their costs appropriate to the provincial divisions, and for each

province there was a military tax register (ketabcheh-ye bonicheh)

in which the method of calculating the tax was stipulated. The chief

muster-master headed finally all muster-masters of the different areas

of Persia and was answerable only to the minister of army (wazir-e lashkar), who mostly was a member of the royal family.

It

was common for some regiments to reach only half or three-quarters of

their strength on paper, though payment from the Treasury for the full

number was collected. Also, the officers of the regiment were entitled

to a share of the soldiers’ wages; as they also often appropriated the padarana,

and sometimes soldiers were even forced to work in the cities in order

to earn their livelihoods. To avoid that the governmental rations would

become only a source of income for the local recruiting sergeant, and

to secure the right running of recruitment and training, regular

inspections took place by the regimental colonel visiting the different

units to report the central government about the troop’s actual

condition and orderly day’s life in the headquarters. Periodical parades and camps held by the shah completed these inspections. (To see a troop’s recruitment - click here.)

With

this recruitment system the central government had about 100,000

infantrymen, 30,000 cavalrymen and several units of artillery under its

command, including the royal guards, musketeers, footmen and the shah's

private household staff. They all were equipped with modern European

weapons, munitions and short westernized uniforms. Only at ceremonial

occasions the high ranking officials still wore the traditional long

uniforms consisting of a long cashmere robe, a wide cummerbund and a

high hat (often a length of embroidered cashmere shawl wrapped around

the common felt skull cap). Red felt pantaloons and flat slippers

completed this formal attire.

During

Nasser od-Din Shah's reign in the course of the 19th century a gradual

institutionalization of bureaucratic positions took place and helped to

raise the relative status of these “men of the pen” (ahl-e qalam) to that of the "men of the sword" (ahl-e seyf). By this fashion, major lashkar-newises were given honorific titles equivalent to those of high-ranking military officers. Thus, Mirza Zaman was honorary called Agha (lit. "Sir") by Nasser od-Din Shah and the former tribal title of Beyg, used in the family’s past, changed in that of a superior Khan (magnate),

according to common Persian customs of calling landowners of old

provenance with this not only hereditary but also adoptive sobriquet.

In

office Agha Mirza Zaman Khan Kordestani "Lashkar-newis" documented in

governmental reports to His Majesty the Shah several lists which

counted all costs and vouchers of payment of the entire soldiery of

200,000 men of that time.

These reports gave the ministry of war an overview about the army's total costs, which amounted to one third of the whole annual fiscal expenditure. Furthermore, Agha Mirza Zaman Khan became military adviser to the shah, was a permanent visitor at court and wrote

books about military history and astronomy, too.

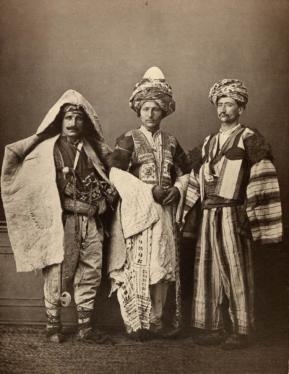

Drawing of the Kurdish Agha of Senneh Oghli Beyg and his photograph where he is surrounded by two tribesmen of the Mokri Kurds in traditional costumes, ca. 1863.

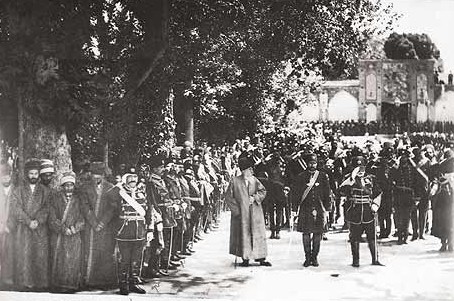

Military

drill parade of an infantry unit at the time of Nasser od-Din Shah: In

the frontline the mounted commander of the troops inspecting the

soldiers.

Army parade at court: The commander-in-chief (amir-e tuman) presents the shah his regiment (right), assisted by his deputy (ajudan) and inspected by the elder of the Qajar tribe (middle). Next to him the staff commander (mir-panj) saluted heading his royal guards, and the leading army clerks, the Mostowfi-ye nezam, the Rais-e daftar and the Lashkar-newis

(left) attended the ceremony.

In

1868 Agha Mirza Zaman Khan Kordestani married Pari Soltan Khanom

Pir-Bastami, daughter of Mohammad Hossein Khan "Mir Panj" and Effat od-Dowleh, and hence grand daughter in paternal line of

Dust Ali Khan "Moayyer ol-Mamalek" and in maternal line belonging to

the Qajar dynasty itself (for this family line see:

The Moayyeri Ancestors). He married in his relatively later years because he was new in Tehran and had there no network there with female relatives who could help him founding a suitable bride. This

was the next familiar connection to a leading Qajar bureaucratic

family of noble blood and another attempt for unification with the

Qajar dynasty itself. It is told within the family that at first the

bride's parents did not want to give Mirza Zaman Khan their daughter's

hand until they were convinced of the Kurdish groom's wealth. So,

sending the necessary gifts of the ring, earrings, cashmere shawls,

wedding sweets and cakes with the marriage contract, Mirza Zaman Khan

came to the marriage ceremony at Mohammad Hossein Khan's house riding a

horse with golden horseshoes to pick up his bride. Finally the shah

even agreed to the marriage and this is why Pari Soltan Khanom

sometimes was nicknamed "Zarrin Khanom" (lit. "Golden Lady") after her

marriage. Becoming the matriarch of our family she gave birth to three

children by Agha Mirza Zaman Khan, two sons and one daughter: Agha Mirza Ali Akbar Khan "Lashkar-newis" "Nasr-e Lashkar", Mirza Ali Asghar Khan (alias H.E.

Ali Asghar Zarrinkafsh)

and Banou Fatemeh Soltan Khanom (alias Fatemeh Afshartous). All three

children were married with close relatives from their mother's side and

members of the Qajar aristocracy and became the founders of the three

family main lines Zarrinnaal (which includes the Zarrinkafsch-Bahman), Zarrinkafsh and Afshartous.

Pari Soltan Khanom Pir-Bastami smoking the water pipe. She was Agha Mirza Zaman Khan Kordestani's only wife. Her paternal cousin Ali Khan Wali took this photograph in Tehran after his visit to Moscow in 1873.

12. Jenab-e Agha Mirza Ali Akbar Khan-e Zarrinnaal "Lashkar-newis" "Nasr-e Lashkar" (1868-1930)

Agha Mirza Ali Akbar Khan "Nasr-e Lashkar", Tehran 1918.

Agha Mirza Zaman Khan Kordestani's eldest son by Pari Soltan Khanom Pir-Bastami was Agha Mirza Ali Akbar Khan-e Zarrinnaal, entitled for his merits in military sector with the title (laqab) "Nasr-e Lashkar" (lit. "Defender of the Army") by the shah. He was born in 1868 at Tehran and died there 1930 on his estates at

Doshan-Teppeh

in eastern Tehran. Like every member of the aristocracy he got an

education next to skills in writing, arithmetic and reading, in the

noble arts of fencing, poetry, hunting, horsing and calligraphy and

then he started military service. At the Tehran military acadamy (madresseh-ye nezam-e dowlati)

he studied weapons technology and martial law. After his studies as son

of a Qajar notable he entered service at court and became, like his

father, military adviser to Nasser od-Din Shah and was honory called Jenab-e Agha (lit. "His Excellency"), as well.

He inherited his father's post and titles as muster-master (lashkar-newis) and became chief secretary of the army 1904 to 1906. Until the end of the Qajar rule 1925 he held several posts as head of the military administration, especially in the Army Law Court Department (majles-e mohakemat-e vezarat-e askari) of the Ministry of War (vezarat-e jang). Under Mozaffar od-Din Shah Qajar (r. 1896-1906) and Mohammad Ali Shah Qajar (r. 1906-1909) he was military instructor to the Persian troops 1906 to 1909 and after it host inspector with the military rank of a nazem (inspector) 1909 to 1915. As well, at the time of Mohammad Ali Shah he became conservative politician in the first national assembly which later constituted in the first Iranian parliament or Majles on 7th of October 1906. With the nickname "Kordi" he was a delegate for Kurdistan and one leader of the royalist conservative wing (etedahiyun), supporting Mohammad Ali Shah's efforts to return to absolutism, because both men feared that the British dominated parliament could strengthen more English influence in Persia. (History shows us that they were right when after the Russian Revolution England got ultimate access to influence and power in Persia and governed the country quasi as protectorate.)

He inherited his father's post and titles as muster-master (lashkar-newis) and became chief secretary of the army 1904 to 1906. Until the end of the Qajar rule 1925 he held several posts as head of the military administration, especially in the Army Law Court Department (majles-e mohakemat-e vezarat-e askari) of the Ministry of War (vezarat-e jang). Under Mozaffar od-Din Shah Qajar (r. 1896-1906) and Mohammad Ali Shah Qajar (r. 1906-1909) he was military instructor to the Persian troops 1906 to 1909 and after it host inspector with the military rank of a nazem (inspector) 1909 to 1915. As well, at the time of Mohammad Ali Shah he became conservative politician in the first national assembly which later constituted in the first Iranian parliament or Majles on 7th of October 1906. With the nickname "Kordi" he was a delegate for Kurdistan and one leader of the royalist conservative wing (etedahiyun), supporting Mohammad Ali Shah's efforts to return to absolutism, because both men feared that the British dominated parliament could strengthen more English influence in Persia. (History shows us that they were right when after the Russian Revolution England got ultimate access to influence and power in Persia and governed the country quasi as protectorate.)

During the reign of the last Qajar ruler Soltan Ahmad Shah (r. 1909-1925) he was senior public prosecutor at martial court (moddai ol-omum koll-e nezam), which was instituted 1915 by Prince Abdol Hossein Mirza "Farman Farma" as minister of justice and war, with a high monthly salary of 111 tuman

1915 to 1925. For his loyal service to the Qajars he got parts of

Nasser od-Din Shah's imperial hunting area east of Tehran, called Doshan-Teppeh. This sandy area (shanzar)

became the immobile base for the family's wealth, when it was

cultivated in the days of Reza Shah Pahlawi by Nasr-e Lashkar's sons

and villas and summer residences of Tehran's court elite were built

there, naming it "Zarrinnaal-District" (mahalleh-ye zarrinnaal). It was situated next to Meydan-e Baharestan (Baharestan-Square) with the Parliament Building (called Baharestan lit. "Place of Springtime") directly behind the old Shemiran-Gate, at a quarter between the Khiyaban-e Baharestan and Khiyaban-e Mazanderan, Khiyaban-e Vahid Dastgerdi and Khiyaban-e Jaleh (today Khiyaban-e Mojaheddin-e Eslam). The two main streets were the

Khiyaban-e Zarrinnaal ("Avenue Zarrinnaal" today Khiyaban-e Shahid Homayoun Nateqi) and Khiyaban-e Khorshid ("Avenue Khorshid" today Khiyaban-e Shahid Meshki). Therefore,

coming from Kurdistan, in our family you cannot only find the founders

and first settlers of the city of Sanandaj but also we were

participated in the creation of parts of the

Iranian modern capital of Tehran, and then formed a quarter of Shemiran with some streets, alleys, clubs and parks and a public school named after until the Islamic Revolution in 1979...

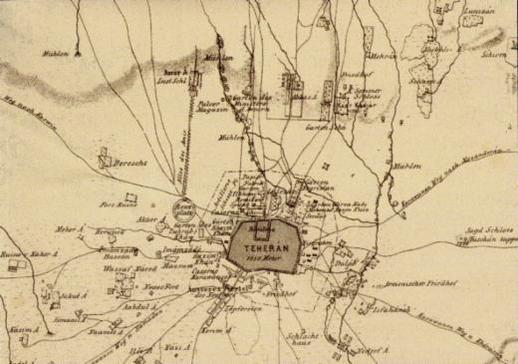

Map

of the city of Tehran with all outer districts and the old mud-walled

centre from the time of Nasser od-Din Shah. Far right the "Jagd Schloss Toschán tappe" that is Doshan-Teppeh.

Ali

Akbar Khan's maternal relatives on a trip at Sanandaj. Left to right:

Dignitary of Sanandaj, Mohammad Hossein Khan "Sardar" (Ali Akbar's maternal grand father), his laleh, Ali Akbar Khan as a young boy, N.N., Mohammad Khan Wali (Ali Akbar's maternal cousin and later father-in-law), Ali Khan Wali (Mohammad Khan's brother and the later governor of Sanandaj).

The Teheran Military Academy with the cadet class. Mirza Ali Akbar Khan is standing right next to the cannon.

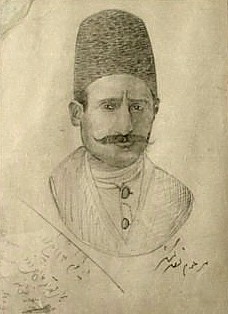

Young

graduate of the Tehran military academy in full uniform in 1885, and

Nasr-e Lashkar as a magistrate. This drawing was made by Nasr-e

Lashkar's younger brother Ali Asghar Khan.

The court officials of Nasser od-Din Shah Qajar 1890 including Nazm od-Dowleh Rais-e Polis, Seyf os-Soltan, Bashir ol-Molk "Shatar-bashi", the Crownprince Mozaffar od-Din Mirza, Agha Mohammad Ali "Abdar-bashi", Abdol Hossein Mirza "Farman-Farma", Baha od-Dowleh, Nasser od-Din Shah, Kamran Mirza "Nayeb os-Saltaneh", Agha Bala Khan "Sardar-Afkham" and far right with a fur linned sardari-coat Agha Mirza Ali Akbar Khan "Nasr-e Lashkar".

The

first Salaam of Soltan Ahmad Shah Qajar in 1909: In the window there is

the young shah with his uncle and regent receiving congratulations of

his subjects, under the window the Officers in Duty and Agha Mirza Ali Akbar Khan "Nasr-e Lashkar" in the rank of Nazem or Inspector with sash and a breast star as Chief Disciplinarian of the Army and Host Inspector.

Agha

Mirza Ali Akbar Khan "Nasr-e Lashkar" was married four times and had

issued ten children, seven sons and three daughters. Thus, he became

the patriarch of our large family, originally named Zarrinnaal in 1930 when family names were officially mandated by the government.

First he married in 1883 Marziyeh Khanom (later called Massoumeh), who died early in Tehran and was the mother of his eldest son Mohammad Ali

Khan "Nasir on-Nezam" (lit. "Protector of the Soldiery"), b. 1884.

In

1893 he married his second wife, his maternal second cousin Roghiyeh

Khanom Wali, the elder daughter of Mohammad Khan Wali by Bibi

Hajjar Khanom (for this family line see: The Wali Ancestors). She gave birth to Javad (Ali) Khan (called Dadash Khan, b. 1894), Kazem (Ali) Khan (called Dadash Mirza, b. 1896), Davood (Ali) Khan (called Dadash Agha, b. 1899), Jafar Khan (b.1900), Mehdi Khan (b. 1902), Ahmad Khan

(1904) and Talat al-Molouk Khanom (1898). When she suddenly died by

infection in 1910 Nasr-e Lashkar once more became a widower with a

family to raise, he decided to marry from the same family again, for

his own sake and to have a mother for his children. So he married

Roghiyeh's young full sister Ameneh Khanom Wali in 1910, who

unfortunately died as well in 1913 and who was the mother of Malek-Taj (Zarrin-Malek) Khanom (b. 1911). Roghiyeh Khanom and Ameneh Khanom were regarded due to their high social position as his two main spouses.

Then he married his last wife Nayereh Khanom Zarrinnaal, a commoner and daughter of a local Seyyed by his wife Zan Agha. She became the mother of his youngest daughter Sakineh Zarrin-Homa Khanom (b. 1913). Nayereh Khanom was a pious, warm and friendly woman, always veiled by her light house chador. She lived with her mother and young daughter in her own house in the middle of the Zarrinnaal quarter next to a very old holy tree, the Derakht-e Morad, where the cildren always gathered to play. Her mother Zan Agha in that time was a woman of more than hundred years without eye lashes anymore. But she was very popular among the family's children, forbid them to climb on the holy tree but also gave them always sweets, and told them several fairy tales and heroic legends of the past.

For more information about the several family branches see: Family Trees.

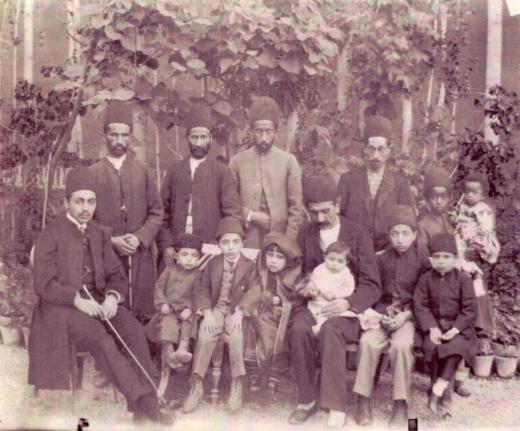

Nasr-e Lashkar's family at Tehran 1903. Sitting from left to right: Mohammad Ali Khan "Nasir on-Nezal", young Jafar, Kazem, Talat ol-Molouk, Agha Mirza Ali

Akbar Khan "Nasr-e Lashkar" with Baby Mehdi, Javad and Davood. Behind

the family Nasr-e Lashkar's attendant, secretary, servants and a black

slaveboy with baby.

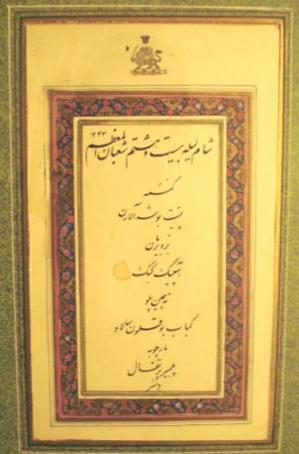

Invitation to a Royal Gala Diner at court with the menue, Sha'ban 1343 (February 1925).

To continue to The Pahlawi Era - click here

This website was created by Arian K. Zarrinkafsch (Bahman-Qajar).