| IQSA Article - "Heraldry" IQSA Article - "Transition" MA Paper - "Wandel im Erscheinungsbild" | The Zarrinkafsch-Bahman (Qajar) Family |

The Coat of Arms of the Zarrinkafsch-Bahman family.

The

coat of arms depicts in blue on a silver rock resting on green ground,

a lying silver lion, across its back a golden rising sun. The shield is

covered by a lion skin and topped by a golden crown around a red

headgear. The

coat of arms was inspired by the old royal Persian emblem with a

crouching lion, but instead of the golden royal lion it was replaced by

a silver coloured one, to distingiush the Zarrinkafsch-Bahman line from

the line of the Royal House. Also the lion still lies and does not hold

any sword in its paw like the later Qajar one. It was created in

commemoration of the several marriages with the Qajar Dynasty.

The

Iranian Heraldry: A Research about the History of the Qajar Coat of

Arms and the Forgotten Tradition of Iranian Heraldic Art in Persia

by Arian K. Zarrinkafsch-Bahman

When

I met for the first time Ferydoun Barjesteh, the vice-president of the

International Qajar Studies Association (IQSA) and editor-in-chief of

the annual Qajar Journal, and his wife Dr. Sahar Barjesteh-Khosravani

at the family gathering in the Netherlands 2002, I recognized that they

wore, just like me, signet rings showing their coat of arms. I asked

myself if these rings are just fashionable acessories acquired from the

Europeans to express our aristocratic lineages, or does there exist an

own Iranian tradition in having coat of arms? We are not European so

why should we imitate European style of noble attitudes! It was (and

still is) very popular in European dynasties and old families to show

nobility and high social position by wearing such signet rings.

In

Iran, as everywhere else in the world, it was an old tradition to mark

something with a special sign to make sure to whom it belongs or to

seal documents, officials or non-officials. Thus, naturally everyone

had his own seal.[1] But

did there also exist special symbols of a common group like a family,

tribe or social community? Because of this question I decided to write

an article about Iranian heraldry.

Fig. 1

Achaemenidian signet rings

of Persian dignitaries,

dated 4th century BC.

Left a battle scene between

a Persian and a Barbarian,

right a mythological animal.

Hermitage Museum, Saint

Petersburg.[2]

Achaemenidian signet rings

of Persian dignitaries,

dated 4th century BC.

Left a battle scene between

a Persian and a Barbarian,

right a mythological animal.

Hermitage Museum, Saint

Petersburg.[2]

Beside

the well-known and famous crown jewels, the Imperial crown and the

coronation throne (the so called "Peacock Throne"), also the symbol of

the lion and the sun (shir-o-khorshid) belongs to the regal attire and the imperial image of the Persian court, especially in the Qajar era.[3]

Later this royal or regal symbol became also the emblem of the Royal

House itself and the Imperial Family as well as it became symbol of the

state and land of Iran. It even survived the Qajar dynasty but with the

Pahlawi's downfall it became finally a symbol of Iran's absolute

monarchy when damned and replaced by the Islamic revolution in 1979.

In the 19th century, different versions of the lion-and-sun emblem became coat of arms of several provincial cities [4] in Iran, as well as families close to the Qajar royal house adopted these symbols, too.

But

where can we find the traditional roots of that so called "heraldry" in

Qajar time and over that; it is again an adaption to a European model

or something genuine Iranian?

Indeed

the Iranian heraldry has a quite older history than the European and is

probably based in the time of the fifth century BC, when once more,

Indo-Iranian (Aryan) nomads were coming on horsebacks out of the

inner-Asian steppes and Transoxania to migrate and settle down in the

region north of nowadays Iran. Those Iranian peoples did not only bring

their religion and myths to the country, the base of the future popular

Persian legends[5],

but also social and strategic innovations. Their tribal leaders of a

well trained and heavy armoured cavallery became in future times the

top of a stringent classified feudal aristocracy. To be recognized also

by friends and enemies during the war times behind their armours, but

also to ask heaven for help, those commanders would mark their weapons

with special signs. That was what the princes from the Iranian People

of the Scyths (Sakes) did. They marked at first their shields with

animal symbols, maybe as an apotropaecial symbol of protection. Later

such holy animals functioned as arms of each dynasty. The Scyths had

contact to the Achaemenidian Empire and did not converted to the

monotheism of Zarathustra's new religion like the Persians did, but

kept their old faith, believing in old Iranian godheads and spirits.

The leaders of these esquerian armies in northern Iran entreated their

gods and guardian spirits for assistance in battle by decorating

themselves and their horses with images of family totems or gods'

symbols.[6]

But the Scyths took over from the Achaeminians the shape and kind of

their own shields, covered with animal decorations as well. In this way

this apotropean animal became the weapon by being fixed to the shield

very clearly and by being well visibly carried in front into the battle.

Fig. 3 and 4

Golden fish on a Scythian

shield and golden shield

bulge with bulls, lions, rams,

panthers and goats, 500 BC,

found in a Scythian prince's

tomb near Vettersfelde,

eastern Germany.

Golden fish on a Scythian

shield and golden shield

bulge with bulls, lions, rams,

panthers and goats, 500 BC,

found in a Scythian prince's

tomb near Vettersfelde,

eastern Germany.

Fig. 6

Golden dagger's sheath with

the same animals. Most of the

depicted animals were also

hunted and probably dedicated

to some nature gods, but the

fish could have been the holy

animal of the prince's dynasty

like a heraldic emblem.

Golden dagger's sheath with

the same animals. Most of the

depicted animals were also

hunted and probably dedicated

to some nature gods, but the

fish could have been the holy

animal of the prince's dynasty

like a heraldic emblem.

Especially

the Scyths from the Black Sea coast show this tradition. So during the

Migration of the People, the Iranian Alanes left their home at the

Black Sea in the fifth century AD and came to Western Europe, where

they finally settled near Orléans and in Spain. In the second half of

the 12th century AD, heraldry, as we know it today, found origin in

this region of France and was exported by the Flemish all over Europe

in the Middle Ages. This suggests the possibility, that the tradition

of European heraldry could be brought to Europe by the Alanes and

started in old Iranian faith.[7]

To

look for the roots of heraldry in Iran we also have to take a look at

the history of flags, because there is a close connection between both

of them and most state arms of the world appear as a badge on their

flags, too.[8]

Although the first recorded flag of Iran was the apron of the

blacksmith Kava who led according to legends in mythological time the

resistance to king Zahak, other standards and flags must have been in

use before them.[9]

Indeed the probably oldest flag known to archaeology was found on the

site of Khabis, East Iran, in 1972, and dates back five thousand years.

It is a metal standard, with a finial in the form of a spread eagle and

a square field incised with religious or mythological motifs. The eagle

finial is similar to those used in modern German or American flags; and

Iran's own modern national symbol, the lion and sun, figures in the

field's design.[10]

Fig. 7

Iranian metal flag, in which two

lions and a sun were incised

among other mythological

emblems. Khabis, 3000 BC.

Iranian metal flag, in which two

lions and a sun were incised

among other mythological

emblems. Khabis, 3000 BC.

In

Iran's ancient times animals were not only objects of hunting but also

responsible for personal protection. This is proved by the fact that

animals' figures were not only engraved in seals to use for practical

purpose but also used as amulets and shown on vexilloids and flags the

same way. It seems that the popularity of such animals as personal

signs has got close connections to warriordom, because several animal

figures have been worn as helmet decorations, and knightly warriors

identified themselves with their animals.[11]

Very popular were certain symbols of those special holy animals dedicated to a single god. Often the gods were incarnated in these animals and according to myths they walked on earth to help men in these personifications.

Very popular were certain symbols of those special holy animals dedicated to a single god. Often the gods were incarnated in these animals and according to myths they walked on earth to help men in these personifications.

Fig. 8

Sasanian seals showing some

holy animals of Iranians like the

horse, eagle and ram.

British Museum, London.[12]

Sasanian seals showing some

holy animals of Iranians like the

horse, eagle and ram.

British Museum, London.[12]

According to Avesta[13]

the same animals, horse, ram and also boar are forms of the divine

spirit Verethragna, engaged in the conflict between Good and Evil. The

boar that kills with a single stroke the objects of veneration and

sacrificed in the hunt was Mithra's avenger who punished liars.[14] The horse even stood for God Ahura Mazda,

the "Wise Lord", the world's creator anf highest god, it was the holy

Persian animal and mostly honoured since the Achaemenians. The eagle

was the symbol of the divine lady Anahita, mistress of heaven and of

fertility. Thus, these animals could be use as emblems by whom who felt

close to their divine personifications. For instance, the royal family

in Sasanian time wore headresses and helmets crowned by protomes of

these animals as seen on several coins and metalwork.[15]

[15]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn15 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn15 Datei [ Bytes]

Fig. 9

Antinoe silk, a standing ram,

7th century. Museé Historique

des Tissus, Lyon.

7th century. Museé Historique

des Tissus, Lyon.

Fig. 10

Boar's head fragment, from

Boar's head fragment, from

Astana, Soghdian, Transoxania,

7th century. National Museum,

New Dehli.

7th century. National Museum,

New Dehli.

Fig. 11

Silver coin of Shah Bahram II.

Queen Shapuhrdukhtat and

the crown prince wear animal

decorations at their hats. Iran,

Sasanian, 3rd century.

The British Museum, London

Silver coin of Shah Bahram II.

Queen Shapuhrdukhtat and

the crown prince wear animal

decorations at their hats. Iran,

Sasanian, 3rd century.

The British Museum, London

Thus

in Sasanian time (224-652 AD) the soldiers at first practice the same

traditions than the Scyths before and perhaps the Achaemenians, too.

They decorated their shields and helmets with divine symbols of

protection. But beginning with the Sasanian rulership in Fars and their

conquest of the whole Parthian Empire, the dynasties changed with a

renovation in warfare, too. The light armed Parthian horsemen were

defeated by heavy armoured Sasanian cataphract cavallery. In Sasanian

time society based on a feudal system. That means that the vassals had

to serve for their liege in war and paid their weapons with a part of

their fief's yield. This system made possible that the soldiers were

ready to move into war at any time, had an expensive equipment and

could be totally covered by armour, like European knights. But now

there was no possibility to identify them. Because of this

non-recognisability the armours also were surfaced with special marks

and signs to recognize the knights under it (often members of the royal

family or higher nobility). Thus, shields were painted with figures

sometimes. But quite often special symbols (gods or animals) appeared

on helmets, banners or flags, not only in a religious context as

before, but to mark their bearer actually.[16]

[16]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn16 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn16 Datei [ Bytes]

Fig. 12

"The Knight in the Great Grotto":

Half-plastical sculpture of Shah

Khosrow II.,Taq-e Bostan, Iran,

Sasanian 7th century.

This sculpture makes clear that

the Sasanian knights looked

pretty much like their European

counterparts six centuries later.[17]

"The Knight in the Great Grotto":

Half-plastical sculpture of Shah

Khosrow II.,Taq-e Bostan, Iran,

Sasanian 7th century.

This sculpture makes clear that

the Sasanian knights looked

pretty much like their European

counterparts six centuries later.[17]

[17]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn17 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn17 Datei [ Bytes]

Fig. 13

"The Battle of Firuzabad": This

relief shows the battle of Arda-

shir I. and his son Shapuhr I.

with the Parthian Artabanos IV.

Firuzabad, Iran, Sasanian 230

AD. The helmets of the Sasanian

warriors are decorated with special

signs which also surfaced their

armoured horses.[18]

relief shows the battle of Arda-

shir I. and his son Shapuhr I.

with the Parthian Artabanos IV.

Firuzabad, Iran, Sasanian 230

AD. The helmets of the Sasanian

warriors are decorated with special

signs which also surfaced their

armoured horses.[18]

[18]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn18 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn18 Datei [ Bytes]

Ferdowsi says in his half-narrative half-historical based Persian national epic Shahnameh ("Book of the Kings") that each noble Iranian family had fought under its own animal or emblem.

[19] As

well as every single Sasanian king used his own individual shape of

crown, which was decorated with special signs dedicated to the single

god the king felt close to or by whom he felt provided with power[20],

the noble families of the empire used these special divine signs as

symbols for their own houses, too. So everyone could recognize both;

the king by his special crown on a coin e.g., and the family by its

banner with the special sign or coat of arms, respectively. According

to Ferdowsi these banners were put in front of the commander's tent

when the families served in war.[21] So

there might be relations between the Iranian holy animals (e.g., horse

for the Persians, goose for the Soghdians) and these heraldic animals.[22]

[19]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn19 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn19 Datei [ Bytes]

[20]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn20 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn20 Datei [ Bytes]

[21]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn21 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn21 Datei [ Bytes]

[22]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn22 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn22 Datei [ Bytes]

Different

miniatures show vividly battle scenes between Iran and her enimies. The

banners of the parties were descriptived flattering in the wind.

On a miniature of the famous Shahnameh version by Shah Tahmasp (r.1524-1555), we can see Prince Forud who confronts the Iranians.[23] The Iranians make war with Turan and march against Forud's fortress Kalat. The hero Tus is the Iranian lord and leader and rides in front of his troops. Next to him one of his knights carries Tus' banner: on green a golden elephant as his device. On another version, made in the reign of the Timurid prince Baysonghor, you can see a battle scene showing Rostam and the Khaqan of Tshin (i.e., king of China).[24] The artist depicted each army with its own banner. The Chinese standard shows in vermilion a golden dragon with a golden phoenix, the old popular Chinese emblem. The Persian standard shows on white ground the Simourgh, the mythological female phoenix-bird. It is the banner of Rostam, king of Zabolistan and Iran's vassal and greatest warrior, which also appears on the hero's quivers.[25]

On a miniature of the famous Shahnameh version by Shah Tahmasp (r.1524-1555), we can see Prince Forud who confronts the Iranians.[23] The Iranians make war with Turan and march against Forud's fortress Kalat. The hero Tus is the Iranian lord and leader and rides in front of his troops. Next to him one of his knights carries Tus' banner: on green a golden elephant as his device. On another version, made in the reign of the Timurid prince Baysonghor, you can see a battle scene showing Rostam and the Khaqan of Tshin (i.e., king of China).[24] The artist depicted each army with its own banner. The Chinese standard shows in vermilion a golden dragon with a golden phoenix, the old popular Chinese emblem. The Persian standard shows on white ground the Simourgh, the mythological female phoenix-bird. It is the banner of Rostam, king of Zabolistan and Iran's vassal and greatest warrior, which also appears on the hero's quivers.[25]

[23]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn23 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn23 Datei [ Bytes]

[24]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn24 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn24 Datei [ Bytes]

[25]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn25 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn25 Datei [ Bytes]

The Simourgh had often helped Rostam's family and so became here its symbol likely.

Fig. 14 a. and 14 b.

Two Iranian banners showing

their bearers' devices:

a. Foroud confronts the Iranians,

miniature of the Shah-Tahmasp-

Manuscript, Tabriz ca. 1520-1530.

b. Rostam lassoes the Khaqan of

Tshin, miniature in the Baysonghori-

Manuscript, Herat 1430.

their bearers' devices:

a. Foroud confronts the Iranians,

miniature of the Shah-Tahmasp-

Manuscript, Tabriz ca. 1520-1530.

b. Rostam lassoes the Khaqan of

Tshin, miniature in the Baysonghori-

Manuscript, Herat 1430.

These

two pictures are both examples that there indeed has existed an Iranian

heraldic tradition in pre-islamic time, which also turns up in Persia's

art of Muslim time, even if it is restricted in descriptions of

legendary family arms like here. But they are based nevertheless on

historical examples.

But now the question is what happened to it after the downfall of the Sasanian Empire?

With

the Islamic inroad of the Arabs into Iran in the seventh century the

old symbols disappeared in the same way as the ancient religion was

driven out and superseded. Thus, under Islam and its strict refusal of

any figurative image, Iran went a new way, and this former kind of

religious inspired "heraldry" was not carried on furthermore for the

next centuries. Since Islam has strong injunctions against the

representations of living things, such decorations are rare in the

early time and are more common to Persian than Arab traditions. As

might be expected, Muslim flags and seals rely on graphic design and

calligraphy rather than on the beasts and flowers which tend to

predominate before in Iran, respectively. During the crusades the

Muslim soldiers put different coloured cloths at their lances to differ

themselves from the Christian knights.[26] So Islamic strictures against representational art encourage the

development on flags of abstract patterns and calligraphic design in

embroidery, appliqué, or painting. Moreover the Arabs seemed to have

invented the concept of associating specific colours with dynasties and

individual leaders. This latter concept very gradually became the basis

for all modern flag designs. The prophet Mohammad at least used two

flags, one white and another black.[27] The

colour green was the colour of Mohammad's Kureish tribe and became the

colour of his own family, lately most popular as the flag of the House

of Ali and the symbol of the Shiites. The Abbasid Caliphs, who

originated from and had their headquarters in Persia, used a black flag.[28]

[26]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn26 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn26 Datei [ Bytes]

[27]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn27 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn27 Datei [ Bytes]

[28]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn28 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn28 Datei [ Bytes]

Later

in Islamic times the seals showed phrases from Holy Koran or the

bearer's name in Arabic letters, but sometimes figural seals were used

again.

Fig. 15 and 16

Islamic seals from the

14th century. A rare

seal depicting a lion

(left),

one with the name

and titles of the Timurid

emir Miran Shah (right).

Hermitage Museum, Saint

Petersburg.[29]

Islamic seals from the

14th century. A rare

seal depicting a lion

(left),

one with the name

and titles of the Timurid

emir Miran Shah (right).

Hermitage Museum, Saint

Petersburg.[29]

[29]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn29 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn29 Datei [ Bytes]

Nevertheless

under Muslim rulership in the region of the former Persian Empire with

the renaissance of Iranian culture traditional arms were also used as

figurative remarkable symbols of their bearers. For instance, the eagle

(later known as "Eagle of Saladin") was used as coat of arms by the

Seljuq sultans and then assumed by most of the modern Arabic states. In

ancient Persia this animal was the personification of the divine glory.

However, the most used animal emblem was the lion. The Avesta book

says, the lion is the symbol of warlike and destroying power.[30] For the old Persians it was the day's power of sun which drove away the darkness of night.[31] Lion

and sun "...refer to ancient symbols of royal lineages and divinity;

the sun (is) a symbol of solar deities and..solar lineages.."[32] Both

also are ancient symbols of royalty as the sun is the ruler of heaven

and the lion is ruler of the animals. In all cultures the lion as ruler

of the animals also represented the king as ruler of men.[33] In

Persepolis there are antique Persian sculptures showing a lion in

battle with a bull. It shows the old combat between day and night or

light and darkness.

[30]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn30 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn30 Datei [ Bytes]

[31]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn31 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn31 Datei [ Bytes]

[32]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn32 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn32 Datei [ Bytes]

[33]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn33 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn33 Datei [ Bytes]

Fig. 17

Persepolis, relief from the

Apadana of Darius the Great.

Apadana of Darius the Great.

Thus,

there still is an early connection between lion and sun in Iran. And

these symbols are the most used in the art we can call modern Iranian

"heraldry".[34] The

double-symbol of lion and sun itself has astrological references to the

constellation of Leo and its ascendary when the sun is in Leo.[35]

When the zodiac of Leo is in sun, appearing in summertime in the Persian month of Mordad (July/August), the Lion as a term for "sun" and "summer" becomes a symbol of the growing power of flora and fauna, of nature's rejuvenation, of rebirth or recarnation and finally of immortality, too. Actually, this is the meaning of the term Mordad. The Pahlavi form of this word is "Ameretat", the name of an old Iranian deity who supports all plant life and represents immortality. 'Mer' or 'Mar' (marg in modern Persian) means death, ‘a’ at the beginning of any word changes the meaning into the opposite, and 'tat' (dad- in modern Persian) is the principal form of the verb dadan "to give". Thus, 'A-mere-tat' gives no death, that means immortality.

This meaning of power und immortality we can also found in the lion as a religious emblem of nowadays. In Christianity the 'Lion of Judaea' means Jesus Christ according to John's Apocalypse 5,5. In Islam one name of Ali, Prophet Mohammad's nephew and son-in-law, the fourth caliph and first Imam of the Shiites, is 'Lion of God' (Asadollah). Both men were martyrs and both men were symbols for devine faith and devine immortality. Thus, this old and ancient symbol keeps its symbolism until today in our modern religions!

When the zodiac of Leo is in sun, appearing in summertime in the Persian month of Mordad (July/August), the Lion as a term for "sun" and "summer" becomes a symbol of the growing power of flora and fauna, of nature's rejuvenation, of rebirth or recarnation and finally of immortality, too. Actually, this is the meaning of the term Mordad. The Pahlavi form of this word is "Ameretat", the name of an old Iranian deity who supports all plant life and represents immortality. 'Mer' or 'Mar' (marg in modern Persian) means death, ‘a’ at the beginning of any word changes the meaning into the opposite, and 'tat' (dad- in modern Persian) is the principal form of the verb dadan "to give". Thus, 'A-mere-tat' gives no death, that means immortality.

This meaning of power und immortality we can also found in the lion as a religious emblem of nowadays. In Christianity the 'Lion of Judaea' means Jesus Christ according to John's Apocalypse 5,5. In Islam one name of Ali, Prophet Mohammad's nephew and son-in-law, the fourth caliph and first Imam of the Shiites, is 'Lion of God' (Asadollah). Both men were martyrs and both men were symbols for devine faith and devine immortality. Thus, this old and ancient symbol keeps its symbolism until today in our modern religions!

[34]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn34 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn34 Datei [ Bytes]

[35]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn35 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn35 Datei [ Bytes]

Fig. 18

Persian pottery dish with the

twelve signs of the zodiac,

dated 1563. Here the

constellation Leo appears

as lion and sun emblem.[36]

Islamisches Museum, Berlin.

Persian pottery dish with the

twelve signs of the zodiac,

dated 1563. Here the

constellation Leo appears

as lion and sun emblem.[36]

Islamisches Museum, Berlin.

[36]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn36 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn36 Datei [ Bytes]

According

to an old Iranian tale the symbol was created in 1600 by the Safavid

Shah Abbas I (1587-1629), when he conquered Armenia and combined the

Armenian heraldic lion with Persia's sun emblem.

In his paper Tarikh-e shir-o khorshid - The History of "The Lion and the Sun",

Sayyed Ahmad Kasravi states that this tale does not base on any

historical fact. Once, there are coins with the lion and sun emblem in

much more earlier times in Persia. Twice, Armenia lost its independence

before Shah Abbas' reign.[37]

[37]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn37 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn37 Datei [ Bytes]

At

first the unificated lion and sun emblem appeared as a regal symbol in

the thirteenth century AD when the Seljuqs ruled as sultans over Iran.

Before, both elements were used and had a traditional history

descripted by poets like Ferdowsi and Nizami. The legend says that in

the year of the Hejjra 637 (1240 AD), Sultan Ala od-Din Kay Kobad

passed away and Khajas od-Din Kay Khosrow became his successor. He

married the daughter of a Georgian prince, and he was so in love with

this Christian princess, that he ordered to mint the princess' portrait

next to him on coins. But the wise men and religious leaders came to

the sultan and said, his wish seemed to be a sin. But the sultan

answered, instead, they should mint a lion with a long mane, that is

the sultan. The sun, which is rising above his head, is the woman he

loves. Also this constellation shows his horoscope and since this time

lion and sun should be Persia's symbols.[38]

[38]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=E42F7A4179DB1607B00365D0CD83E754

wfxApplication;jsessionid=E42F7A4179DB16[...]

TC113a#_ftn38 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=E42F7A4179DB1607B00365D0CD83E754

wfxApplication;jsessionid=E42F7A4179DB16[...]

TC113a#_ftn38 Datei [ Bytes]

Anyway,

since the 1240's the Seljuqs minted coins with this symbol and it

became the arms of Persia. This shows that the emblem still exists

before the time of Shah Abbas. (It is a funny thing that through all

centuries the sun still bears a human woman's face allthough in Iran

the sun was male, actually! Maybe the reason for this is an old

legend...)

Fig. 19

The first coin with the Persian

emblem, a silver dirham of Kay

Khosrou ibn Kay Kobad, minted

at Siwas, 1240.

The first coin with the Persian

emblem, a silver dirham of Kay

Khosrou ibn Kay Kobad, minted

at Siwas, 1240.

Fig. 20

The last type of such coins,

a ten Rial of Muhammad Reza

Pahlavi, minted at Tehran, 1957.

Actually this type of coins was

minted again in modern Iran

during Muhammad Shah Qajar's

reign (1834-1848).

a ten Rial of Muhammad Reza

Pahlavi, minted at Tehran, 1957.

Actually this type of coins was

minted again in modern Iran

during Muhammad Shah Qajar's

reign (1834-1848).

Up from this time depictions of the lion-and-sun emblem are recorded on several coins minted by various dynasties.[39] 1314 by the Il-Khan Oljaitu Mohammad Khodabandeh (1305-1316), and 1316-1335 by his son and successor Abu Said.[40] Also the Timurid[41]

and Mughal dynasties acquired the emblem and it appeared on several

banners and buildings as a symbol of power. The rulers of the

Aq-Qoyunlou dynasty minted coins with the lion and sun emblem, too.[42]

[39]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn39 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn39 Datei [ Bytes]

[40]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn40 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn40 Datei [ Bytes]

[41]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn41 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn41 Datei [ Bytes]

[42]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn42 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn42 Datei [ Bytes]

Fig. 21 and 22

Tileworks with two examples

of the Persian emblem,

13th[43]and 16th century[44].

Tileworks with two examples

of the Persian emblem,

13th[43]and 16th century[44].

[43]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn43 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn43 Datei [ Bytes]

[44]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn44 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn44 Datei [ Bytes]

Not

only the Seljuqs had used the Persian lion for their arms but also

other rulers in the former Iranian region adopted such symbols of

dynasty and royal power in the time of the Seljuqs. E.g., the coat of

arms of the Shirvan-Shahs shows two pairs of lions face to face[45]

as it is depicted at the minaret of the Djuma Mosque at Baku. The same

lions in chains appears in a carpet, produced before 1450[46],

and dedicated to Qara Yusuf Khan Qara-Qoyunlu, who defeated the

Shirvan-Shah between 1405 and 1410 at Tabriz. Here the heraldic emblem

of the former shah was changed and by the way depreciated to show the

superpower of his Turkoman conqueror and sucessor.[47]

[45]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn45 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn45 Datei [ Bytes]

[46]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn46 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn46 Datei [ Bytes]

[47]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn47 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn47 Datei [ Bytes]

Fig. 23

Detail from the minaret

of the Djuma Mosque at

Baku, Azerbaidjan, shows

the arms of the Shirvan-

Shahs.

Detail from the minaret

of the Djuma Mosque at

Baku, Azerbaidjan, shows

the arms of the Shirvan-

Shahs.

Fig. 24

The Art Institute of Chicago:

Chicago No. 1926.1617.

The same type of heraldic

lions in chains on a carpet,

probably the audience carpet

of the Qara-Qoyunlu dynasty.

Chicago No. 1926.1617.

The same type of heraldic

lions in chains on a carpet,

probably the audience carpet

of the Qara-Qoyunlu dynasty.

(Detail)

Another example for heraldry in the Iranian region is the so called Amida-carpet.[48] In

this carpet the heraldic emblems of two dynasties in Kurdistan were

unified. At one hand the emblem of Abu al-Qasem Nisanid of Amida and at

the other, the emblem of Qara Aslan Orthokid of Hisn-Kaifa.

[48]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn48 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn48 Datei [ Bytes]

[49] The

emir Abu al-Qasem Ali (died 1178) of the Nisanidian dynasty subjugated

Amida (Diyarbakir), Kurdistan, in 1165. A relief at the entrance of the

Ulu Djami at Diyarbakir even shows a lion fighting with a bull, the

heraldic emblem of the Nisanidian dynasty. The lion was the symbol of

Emir Ali, the bull stood for the city of Amida. This image also refers

to the old Persian mythological depictions when day wins over night.[50] During

1170 to 1184 the Nisadinians also possessed Hisn-Kaifa and the short

winged and crossed dragonheads of the Orthokidian predecessor appear on

the carpet, too. The same image appears at the entrance of the Aleppo

citadel, which once had belonged to the Orthokidian fief.

[49]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn49 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn49 Datei [ Bytes]

[50]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn50 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn50 Datei [ Bytes]

Fig. 25

The Amida-carpet depicting

the emblem of the Nisanidian

Abu al-Qasem of Amida and

his heraldic emblem at the

entrance of Ulu-Djami at

Diyarbekir, built in 1165.

(Detail)

the emblem of the Nisanidian

Abu al-Qasem of Amida and

his heraldic emblem at the

entrance of Ulu-Djami at

Diyarbekir, built in 1165.

(Detail)

Fig. 26

The emblem of the Orthokidians

at the same carpet and heraldic

emblem of the Orthokidian Qara

Aslan at the entrance of citadel

of Aleppo.

(Detail)

at the same carpet and heraldic

emblem of the Orthokidian Qara

Aslan at the entrance of citadel

of Aleppo.

(Detail)

During

the Safavid era (1501-1722), Shiism became the national religion and

the Safavid shahs tried to legitimate their rulership at first by

religion and their descent of the Imams.[51] So

we can find rather less depictions, references and connections to other

figurative symbols of sovereignty and power in Iran during this period

than before or after but in other centres of Iranian culture like

Mughal India or Uzbek Transoxania.

[51]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn51 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn51 Datei [ Bytes]

Nevertheless

there are many copper coins of Safavid time showing the emblem. After

Shah Ismail (1501-1524) and Shah Tamasp (1524-1576), who did not use

the emblem because they thought it show the shah's horoscope and were

both not born in Leo, it again appeared on many copper coins with Shah

Abbas I. He, who was born in the sign of Virgin, did not care about an

astrological meaning, minted, among others, the lion-sun on coins and

made the symbol again popular. The same did his successors until the

Afghan invasion.[52]

But the regal insignia on copper coins is not yet comparable with that

we call today a coat of arms. Although, according to Hinz in a French

book about the Persian envoy of Shah Hossein Soltan to king Louis XIV

of France 1715 the lion and sun emblem is depicted as Persia's banner,

there are no more reports by European travellers or foreign envoys

concerning the arms.[53] Also

J. Chardin says in his very popular travel reports about Persia nothing

about this banner, but only that the Persians used flags with Koranic

inscriptions or the "Sword of Ali", the famous zul-faqar.[54]

It is the sword of the Prophet's son-in-law which split when being

drawn from its sheath, but with magical powers. So the lion and sun

emblem was not regarded as an arms or symbol of sovereignty of Iran by

the Safavids like it was by the later Qajars, but more as an insignia

of regal rights for minting coins to demonstrate the superpower of

their rulership.

[52]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn52 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn52 Datei [ Bytes]

[53]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn53 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn53 Datei [ Bytes]

[54]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn54 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn54 Datei [ Bytes]

In

medieval Iran people almost did not bear a surname and men were called

after their tribe they belong to. The tribes' names based on heroic

ancestors, their bearers' original residences or occupation. Like that,

family coats of arms in the common sense, like we know it today,

usually did not exist. Divided in subtribes and clans sometimes tribal

or clan symbols appear to sign a special branch.[55]

[55]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn55 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn55 Datei [ Bytes]

The

early Qajars, named after a certain ancestor called Qajar Noyan, were

also divided in subtribes named after their residences, Ashaqah-bash

("the downstream settlers") and Yukhari-bash ("the upstream settlers").

Both Qajar subtribes were after that also divided in several clans and

the principal lineages of both were the Quvanlu and Davalu [56], so named after their profession their herds became their symbols, visibly and literally.

[56]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn56 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn56 Datei [ Bytes]

But

with the Qajars' assumption to the Persian throne and the coronation of

Agha Mohammad Khan and later Fath Ali Shah, it became again necessary

to create an imperial attire like in ancient time. Again the rulers

used the old Persian emblem (as well as they used again a crown and a

throne, in opposite to their Islamic predecessors). So they emphasized

that the Qajars were the right successors of the Iranian Empire and

made the lion and sun symbol to their own. After the Afshar and Zand

rulers did not use the emblem it was officially taken first as the

Qajar symbol of nationality and then became the state's arms. Fath Ali

Shah sent a flag with Iran's arms to Napoleon Bonaparte, Emperor of the

French, as a gift. This flag shows on black cloth (velvet) the stitched

and embroided standing golden lion with a sword in his right paw and

the sun across its back. Also Gaspar de Ville, a French in Iranian

military service 1812-1813, described the royal coat of arms as a lion

with a sword in its paw and a sun across its back before a blue

background. The same type was used as a standard in battle by Fath Ali

Shah's son and crown prince Abbas Mirza 'Nayeb os-Saltaneh' as

commander-in-chief. Diba states in her book Royal Persian Paintings

that "...According to Drouville, banners and standards in the Persian

army were replaced with ones of European type after the review of

Persian regular troops at Ujan in 1813." [57]

[57]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn57 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn57 Datei [ Bytes]

Fig. 27

The Battle of Prince Abbas

Mirza with Russian Troops,

Iran 1815-16.

Oil on canvas, 230 x 396 cm

Hermitage Museum, Saint

Petersburg.

Mirza with Russian Troops,

Iran 1815-16.

Oil on canvas, 230 x 396 cm

Hermitage Museum, Saint

Petersburg.

In Qajar time (1785-1925) the royal emblem appears on many objets d'art, like dishes, jewels, tilework and buildings. In his book La Perse (Paris

1841) Louis Debeux says on p. 462 that the Persian banner shows a lion

lying before a rising sun. This coat appears on flags and the walls of

castles, as well as on the Imperial order.[58] To create an order of honour, Fath Ali Shah founded the Order of the Lion and the Sun (nishan-e shir-o khorshid)

in 1808. According to the flag, the order shows the emblem as well. At

first two variations were commonly used. The standing lion with a sword

in his paw was used for military division and the passive, reclining

lion for the civil division. Later only the standing type was used as

we know it today. The creation of this order, likewise using the emblem

as decoration, should help to create the royal image and constitute

monarchy's all-presence. Finally lion and sun appear as a component in

royal paintings, e.g. on a portrait of Prince Mohammad Mirza, later

Mohammad Shah, showing the prince in front of a red curtain covered

with repeating badges of the lion and the sun.[59]

[58]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn58 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn58 Datei [ Bytes]

[59]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn59 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn59 Datei [ Bytes]

Fig. 28

Golden coin from the reign

of Agha Mohammad Shah

with the lion-and sun emblem.

Iran, 1796.

of Agha Mohammad Shah

with the lion-and sun emblem.

Iran, 1796.

Fig. 29

Golden dish with the royal

Iranian emblem of the lion

and sun, presented by the

Persians to the East India

Company. Signed by

Muhammad Jafar,

Tehran 1817-1818.[60]

Golden dish with the royal

Iranian emblem of the lion

and sun, presented by the

Persians to the East India

Company. Signed by

Muhammad Jafar,

Tehran 1817-1818.[60]

[60]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn60 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn60 Datei [ Bytes]

Fig. 30

Order of the Lion and Sun,

offered to the East India

Company's envoy by Fath

Ali Shah Qajar, 1828.[61]

Order of the Lion and Sun,

offered to the East India

Company's envoy by Fath

Ali Shah Qajar, 1828.[61]

[61]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn61 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn61 Datei [ Bytes]

Fig. 31

Portrait of Mohammad Shah

Qajar as Crown Prince[62]

Qajar as Crown Prince[62]

[62]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn62 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn62 Datei [ Bytes]

Fig. 32

Tilework at the fassade of

Shams ol-Emareh Palace,

Tehran[63]built in 1860.

Shams ol-Emareh Palace,

Tehran[63]built in 1860.

[63]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn63 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn63 Datei [ Bytes]

Fig. 33

Tilework of Naranjestan

Palace portal, Shiraz[64]

Palace portal, Shiraz[64]

[64]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn64 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn64 Datei [ Bytes]

built in 1881 by Ebrahim

Khan-e Qavvam.

Khan-e Qavvam.

Fig. 34

The emblem with a standing

lion with the sword and the

plumed Qajar crown.[65]

This type was also used on coins

since Mohammad Shah's reign.[66]

lion with the sword and the

plumed Qajar crown.[65]

This type was also used on coins

since Mohammad Shah's reign.[66]

[65]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn65 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn65 Datei [ Bytes]

[66]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn66 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn66 Datei [ Bytes]

The

emblem changed over time from a lion lying on the ground and a rising

sun with a human face above its back, to a lion standing and holding a

sword in its right paw and a sun above its back. We can see the

different types and the development of the emblem very well above.

The

sword in the right paw of the lion appeared in the sixteenth or

seventeenth century, and is now identified as that of Ali, the zul-faqar. In fact, the sabre held by the lion has today a normal shape[67]

but there still exist other depictions. The Safavids introduced the

sword as part of their Shiite-religious and national symbols and it is

fairly recent.[68]

[67]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn67 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn67 Datei [ Bytes]

[68]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn68 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn68 Datei [ Bytes]

At

first both types of emblems were used commonly in Fath Ali Shah's

reign. The standing armed lion as an 'active' symbol represented

military spheres. It appeared on the war banner and also represented

the person of the Shah. The Denesh-nameh bozorg-e Iran

says that in 1846 this type was proclaimed the official emblem of Iran

by Mohammad Shah Qajar. The reclining and 'passive' lion represented

civil spheres and was in use until Nasser od-Din Shah as a symbol of

the sovereignty and the country of Iran. Finally the Qajar crown (Taj-e Kiani)

was put at the top. With the Pahlawis, who adopted the emblem, only the

crown changed from the Qajar crown to the Pahlawi crown.

In

the time of Nasser od-Din Shah (r. 1848-1896) it became necessary to

renovate the style of the emblem again. It appeared now only in the

style of the (former military and 'active') standing lion-and-sun type

with the sword and was used as the officially symbol of the state.

Generally the lion always faces left and holds the sword in its right

paw. However, in a painting at the Royal Collection at St James,

entitled 'Review in Windsor's Great Park in Honour of the Shah of

Persia, 24th June, 1873', signed N. Chevalier and dated 1877, there is

a depiction of the Imperial Standard of Persia, raised in honour of

Nasser od-Din Shah, depicting the lion facing right not left, with the

sun above its back as usual topped by a plumed imperial crown. In his

essay at the Qajar Dynasty Pages, Manoutchehr M. Eskandari-Qajar

describes the flag's colour as "...of old pink to light purplish

colour."[69] He

also states that this "...painting is interesting for two reasons. One

is that this is a rare depiction of the imperial lion shown facing

right not left. (...) The other is that this is one of the first

depictions of an official flag for Persia. Apparently the flag depicted

in the Royal Collection must have been the design of the Qajar Persia

flag at the time of Nasser od-Din Shah."[70] According

to some other European sources, this was not the official flag of

Persia but more the banner of 'His Imperial Majesty The Shah'. Thus the

lion and sun emblem is depicted on red or purple ground or surounded by

red or purple. Because purple was the imperial colour since Safavid

times. We also have seen this type of flag before, during Fath Ali

Shah's reign.[71] Just below this banner is shown in a more "European" style:

[69]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn69 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn69 Datei [ Bytes]

[70]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn70 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn70 Datei [ Bytes]

[71]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn71 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn71 Datei [ Bytes]

Fig. 35

Standard of the

Shah of Persia, 1870.[72]

Shah of Persia, 1870.[72]

[72]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn72 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn72 Datei [ Bytes]

According

to the same sources, the official Persian standard as well shows the

lion with the sun holding a sword on white ground bounded by a green

band.[73] The same flag is shown in a sketch of the Persian pavilion at the World Exhibition in Paris from the turn of the century.[74]

[73]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn73 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn73 Datei [ Bytes]

[74]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn74 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn74 Datei [ Bytes]

Sometimes

the lion is faced left sometimes right and Eskandari adds "...though

this fact may be due to nothing more complicated than the artist's

attempt to render the standard being blown in the wind, thus flipping

the standard from its regular position to one where the lion faces

right not left..." Probably this is what happened. However, at this

time there was no regular system for heraldic matters as in Europe, so

once the lion faced left, once right.

According to the Denesh-nameh bozorge-e Iran

again in 1886 the official Iranian flag was white with one green stripe

at the top and a red one at the bottom, the golden lion and sun symbol

was placed in the middle. Later this became the tricolour with the

proportion of the three stripes one to three.[75] This also indicates that not the Pahlawis created Iran's national flag but the Qajars!

[75]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn75 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn75 Datei [ Bytes]

Fig. 36 and 37

Two examples of the official

Imperial Persian Flag,

depicted in European sources,

1870 and 1902.

Imperial Persian Flag,

depicted in European sources,

1870 and 1902.

Fig. 38

The Persian pavilion in Paris.

The Persian pavilion in Paris.

Originally

these Iranian arms consisted of badges, single arrangements of emblems,

and not of coats of arms in its original meaning. These were more

comparable with the Japanese Mon-system than with those in European

heraldry, actually. But in the late Qajar period, when the British and

Russians got more political and social power, the emblem got a more

European look as the official Persian coat of arms we also know today.[76] Now

the single emblem or badge was put on a shield, sometimes covered by a

coat and topped by helmet or crown. This coat of arms showed under a

blue sky a golden lion with a golden sun across its back which is

holding a silver sword (or sabre) in its right paw and stands on green

ground. The arms of 'His Imperial Majesty The Shah' was created

according to European types. The centre was a shield with the royal

emblem, covered by a heraldic ermine coat and topped with the Qajar

Kiani crown. The shield itself was decorated with a Muslim helmet, the

royal order and six lances. Two gryphons, maybe the dragon-peacock Senmurv of Sasanian time, hold the shield.

[76]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn76 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn76 Datei [ Bytes]

Fig. 39

Detail from an appointment

decree of Mozaffar od-Din

Shah with his coat of arms.

The Persian caption reads:

"Official Imperial court

photographer by appointment

of His Most August and Imperial

Majesty the Emperor of Iran,

Mozaffar od-Din Shah."

decree of Mozaffar od-Din

Shah with his coat of arms.

The Persian caption reads:

"Official Imperial court

photographer by appointment

of His Most August and Imperial

Majesty the Emperor of Iran,

Mozaffar od-Din Shah."

Fig. 40

The Majesty Arms of the Shah,

medallion in a Kerman carpet,

used in the reign of Soltan

Ahmad Shah Qajar, produced

in the 1920's.Atighetchi

collection "Maison del'Iran",

Paris.[77]

medallion in a Kerman carpet,

used in the reign of Soltan

Ahmad Shah Qajar, produced

in the 1920's.Atighetchi

collection "Maison del'Iran",

Paris.[77]

[77]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn77 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn77 Datei [ Bytes]

In the last Qajar years such

carpets as we can see here,

were produced for several

members of the court.

carpets as we can see here,

were produced for several

members of the court.

Aside

the official coat of arms, there was still the arms of the Royal Family

and the Imperial Qajar House itself. An emblem used on their dishes[78],

letterheads, on the official documents of the Qajar courtand sometimes

as jewels at their hats. This familiar arms shows two lions with suns

across their backs holding up the Kiani crown with one paw and holding

the globe in their middle under the other. Eskandari states "...In

addition to the immediate members of the Royal family, some of the

princes such as Prince Mozaffar Firouz and others, have used this

emblem as their personal emblem and added their own initials to it. As

a rule, however, this emblem was for the use of the Royal Family itself

only...".[79]

[78]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn78 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn78 Datei [ Bytes]

[79]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn79 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn79 Datei [ Bytes]

Fig. 41

Royal Emblem of the

Imperial Qajar House.

Royal Emblem of the

Imperial Qajar House.

Maybe

the Qajars did not create the lion-and-sun emblem, but they were the

first to use it as a symbol of imperial power and nationality. So the

dynasty made it popular and it became Iran's state symbol and coat of

arms as much as they chose it as their own insignia and gave it a

certain style. The Qajars also identified themselves with historical

Iranian traditions in succeeding a line of Iranian predecessors. And

families closely connected with the dynasty also adapted different

variations of this emblem and took them as their arms to show their

nobility and relations to the Royal House. So several lines of the

greater Qajar clan used details like the Kiani crown or the

lion-and-sun and combined them with other symbols and devices to

underline their branch. Designed in accordance with fashion of their

time, most of these arms are similar to European creations but they

have an own old genuine Persian tradition.

Unfortunately,

with the conquest of Iran by different peoples, the changes of

dynasties and systems and the revolution many sources were lost not

only by destruction but also by propaganda[80],

as well as the historical continuity in art and culture went lost. So

it is hardly possible to prove the scientific facts and genuine of each

source according with Iranian heraldry.

[80]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn80 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftn80 Datei [ Bytes]

The

facts and sources in this article have shown that there is an own old

genuine Persian tradition in heraldry. Obviously it is not as well

represented in daily life as we know it from heraldry in Europe. But it

was also high cultivated in its special and own way in Sasanian time.

And at least it seems over and above that the Iranian heraldry has

inspired also the European. We can not compare both types of heraldry.

Both find their extinction maybe in warriordom and have a religious

background; one in the old Iranian faith of several gods and spirits

represented by animals or parts of them, the other in European

Christianity and Christian knighthood during the crusades. But they had

a rather different development through the centuries. In Europe coats

of arms belonged to one of the main parts of life and culture in the

Middle Ages. In Iran heraldry and heraldic art were surpressed by the

rules of art in Islamic faith and of course could not find such an

expression. But eventually the heraldry has survived through the

Persian myths in Arabic time and was relaunched with the Persian

renaissance in the early Middle Ages. To summarize these facts one can

see that heraldry was present in Iran from her early times and young

archaeological periods through various dynasties until present time and

found its artistic climax in Qajar era.

The

late coat of arms of Iran, the lion-and-sun emblem armed by an Islamic

sabre was a combination of several aspects of Persian history and

culture. It combined the divine power of monarchy (i.e., absolute

monarchy) from pre-Islamic time, shown in the double symbol of

rulership, lion and sun, with symbols of Islamic faith, the Arab sword,

which the lion hold in its paw. This sword, or more sabre, is not only

a symbol for Islam but more for Shiism, because it is the sword of Ali,

the first Imam. Thus, symbols for monarchy and faith were transformed

in Qajar time to create according to old Persian traditions the State's

arms of Iran like the lion sun stood before 1979. It was nor the symbol

of the Pahlawi monarchy neither of ancient (i.e., pre-Islamic) Iran,

the revolutionary committees stated. It combined both material

rulership and religion, so it is a symbol for Iran's own historical and

Shiite traditions!

So

at the end we have found out that there are three different cultural

centres of heraldry in the world: The heraldry of Europe as we know it

today, the Mon-system of Samurai Japan and finally the Iranian heraldry.

Notes

Notes

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftnref1 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftnref1 Datei [ Bytes]

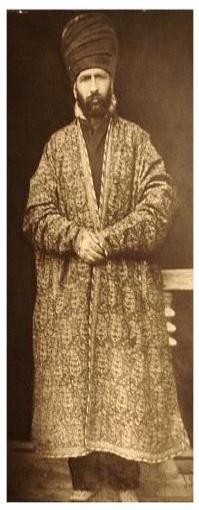

[1] A

good example for such an Islamic signet ring in Qajar time is shown in

the famous portrait of Hussein Gholi Khan-e Qajar Quvanlu, called

Jahansouz Shah, as it is depicted on page 10 of the Journal of the International Qajar Studies Association,

Vol.II, 2002. Unfortunately you cannot see the seal itself very

clearly; maybe it shows a Koran inscription, may be something else.

[1]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftnref1 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftnref1 Datei [ Bytes]

[2]Wladimir Lukonin/ Anatoli Iwanow, Persische Kunst, p. 74.

[2]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftnref2 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftnref2 Datei [ Bytes]

[3] See also Qajar Imperial Regalia and Regal Attire: The Making of Persia's Lion and Sun King Paper

presented at the International conference on "Qajar Era Dress",

University of Leiden, Holland by Manoutchehr M. Eskandari-Qajar, June

2002.

[3]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftnref3 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftnref3 Datei [ Bytes]

[4]Today we know that the narrative circles of the legends about Rostam base on Scythian myths and about the Kiani kings are based on old Parthian myths. Later they were mixed with parts of the Avesta, collected in Sasanian time and finally they had been written down by Ferdowsi in his famous epic Shahnameh.

[4]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftnref4 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftnref4 Datei [ Bytes]

[5]Gerd Gropp, Zarathustra und die Mithras-Mysterien, Katalog der Sonderausstellung des Iran Museum, Hamburg 1993, p.62.

[5]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftnref5 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftnref5 Datei [ Bytes]

[6] G. Gropp, opt. cit., No. 58 ff., p. 66.

[6]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftnref6 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftnref6 Datei [ Bytes]

[7]

The reason for this was that therefore the coat of arms was carried

into war high above the soldiers' heads well visible to everyone.

[7]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftnref7 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftnref7 Datei [ Bytes]

[8] This reasonn Sasanian time this flag of Kava and his Kiani Dynasty was the National Banner of Iran (drafsh-e kiani).

It was taken by the Arabs at the battle of Kadisiya which led to their

capture of the Persian Empire and the introduction of Islam, in A.D.

636. By that time, according to the Arab historian Ibn Khaldun, it was

covered with the signs of Zodiac and lavishly studded with jewels. The

flag was cut into several pieces, sold at the Arabian markets and shoes

were made of it.

[8]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftnref8 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftnref8 Datei [ Bytes]

[9] Whitney Smith, Flags Through the Ages and Across the World, p.34; also Whitney Smith/ Ottfried Neubecker, Wappen und Flaggen aller Nationen, p. 106.

[9]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftnref9 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftnref9 Datei [ Bytes]

[10] See Das Tier in der Kunst Irans, Linden-Museum, Stuttgart 1972.

[10]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftnref10 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftnref10 Datei [ Bytes]

[11] G. Hermann, "The Art of the Sasanians" in The Arts of Persia, p.79.

[11]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9[...]

TC111b#_ftnref11 Datei [ Bytes]

wfxApplication;jsessionid=A9A9D795AC10A9394BB4A30536616CBE